It's a beautiful day in your service area, and your distribution operations control center has few to no outages for operations to deal with; everything at your utility is status quo. Tomorrow, however, a major storm is predicted, so everyone gears up and gets ready to deal with the situation. As the storm impacts your utility's service area, the number and duration of outages exceed expectations, but you are prepared and manage the storm well. The local press coverage is largely positive because you were able to limit the number and duration of outages, which reduced costs and business impacts and left your customers happy about how efficiently your utility handled the situation.

Unfortunately, this scenario doesn’t happen often enough in our industry. Utilities are facing increasing pressures from legislators, regulatory agencies, electricity consumers, and the general public to manage better and communicate on their storm outages and restoration efforts. Key questions include:

- How does a utility achieve successful storm response consistently?

- What are the elements for a well-managed storm?

COMMON SHORTCOMINGS OF STORM RESPONSE

Most utilities have storm process pains resulting in inefficiencies in one area or another. Common shortcomings of storm response include:

- Failure to account for people, system and process changes such as staff retirements and system upgrades

- Inadequate Stakeholder awareness and involvement

- Limiting preparation to the period before the storm season starts

- Insufficient time allocated for preparation and knowledge development

- Lack of role-based training and simulation

- Lack of a comprehensive Storm Response Plan

STORM PREPARATION AND CORRECTIVE ACTION

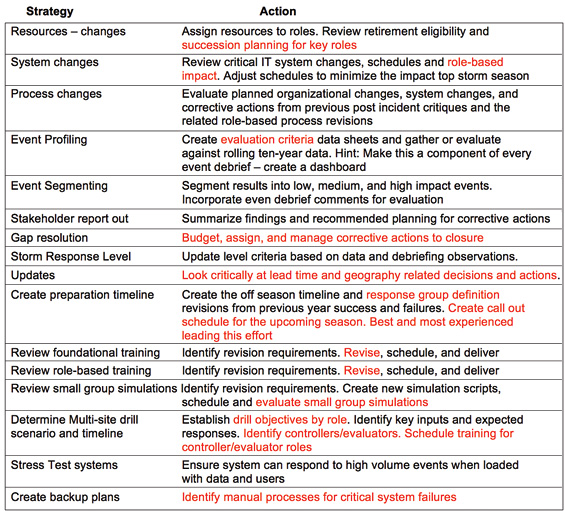

A number of best practices exist for storm preparation and management. These include enabling the right people, systems and processes; In-depth analysis of storm profiles; and leveraging storm simulation technology to provide real-world storm response practice. Table 1 provides a checklist for developing a comprehensive Storm Response Plan.

Table 1: Storm Response Planning Checklist

Items in red are often overlooked or minimized. These items drive storm response consistency and positive media coverage.

People, System and Process Changes

Analysis of people, system and process changes should occur early in the storm response planning process to minimize their impact to successful outcomes when high volume events occur.

A key consideration is the loss of experienced personnel as they reach retirement age. This loss results in a significant reduction in the experience level of the employees that remain and creates a knowledge void that can adversely impact a high volume event.

With regards to systems, utilities are experiencing increases in the amount of enterprise technology and the related changes that get implemented in the lifecycle of their management systems. These systems can include:

- Geospatial Information Systems

- Mobile Workforce

- Energy Management System, Distribution Management System, and Outage Management System

- Radio / Phone Communication Systems

- Work Management System

- Damage Assessment Tools

The timing of implementations, upgrades, and the need for training end users must be a key consideration. The proficiency required using the technology during a ‘blue sky day’ is very different than during a ‘high volume event.’

Process change occurs when the utility makes organizational changes or system changes to adapt to business needs or challenges. These changes are commonly overlooked when preparing for high volume events.

Storm Profiles and Past Event Analysis

All utility stakeholders, from executives to storm responders, need to understand the types and frequency of system events and storms. Reaching back as far as ten or more years can provide a realistic picture of how events have impacted the business.

When developing storm profiles, measure the following types of variables:

- Event type

- Date of event (time of year)

- Prep Time – the time from event awareness until the event impacts service territory

- Escalation time – the time from event start until event peak

- Number of customers out of power at event peak

- Duration of event peak

- Average customer minutes of interruption

- Number of line crew personnel responding

- Volume of Assets Damaged (# poles, #OH transformers, # cross-arms, # insulators, miles of conductor, etc.)

Clustering storm profiles by event type and analyzing the data to segment type and impact provides a number of benefits for planning purposes. For example, the most typical event types can be identified, along with the time of year they occur. The average length of low, medium, and high impact events can be established. For each type of event, analysis will indicate the average lead time before the event and the average number of line crews utilized in past response efforts.

Knowing the typical event profiles and then segmenting the event profiles into categories by event type can assist in planning for future events. This analysis provides data based evidence that will assist in validating post-event critiques and determining corrective actions. With this information, response profiles can be created and leveraged in planning, training and drills.

TIP: Make storm profile data available after every event as a component of post-incident critique, from the dashboard.Use this data to identify improvement opportunities and practice corrective actions in exercises.

Storm Response Level Updates and Geographic Considerations

Storm response level criteria should be reviewed and updated annually based on the profile data and debriefing observations. The following is a typical example of a four level criteria for event activity that drives the utility response taking into account duration, impact to utility-system wide and geographically, weather type, and severity:

- Level 1: <15,000 customers out of power; Light damage to the distribution system; Limited lightning with intermittent wind/rain; Winds less than 20mph with gust under 30mph; Isolated areas of impact with a predicted short duration forecasted.

- Level 2: 15,000 to 50,000 customers out of power; Multiple areas impacted with less than 25 percent impact to transmission or distribution systems; Weather impacting wider range with sustained winds of 30-35mph and gusts up to 40mph; Impact is over region or widespread multiple small geographies; Weather event is slow moving with a 4 to 13 hour duration forecasted.

- Level 3: 50,000 to 150,000 customers out of power; Multiple areas impacted with greater than 25 percent impact to transmission or distribution systems; Weather impacting majority of the service area with sustained winds of 40+mph and gusts up to 50mph; Impact to most of region or widespread to multiple large geographies; Weather event is slow moving, heavy rain, tropical depression, hurricane or tornadoes predicted with 12 hour or longer duration forecasted.

- Level 4: <150,000 customers out of power; Multiple areas impacted with greater than 50 percent impact to transmission or distribution systems; Weather impacting entire service area with sustained winds of 45+mph and gusts over 55mph; Impact to entire region or widespread to multiple large geographies; Weather event is slow moving, heavy rain, tropical depression, hurricane or tornadoes predicted with 24 to 48 hour or longer duration forecasted.

The important take away is that these level definitions come from the analysis of storm profile data and corrective actions from previous experiences. The decision to open storm bases, activate mutual aid, activate the emergency operations center, etc. is based on past experiences and successes or failures. For early success when augmenting the response staff, make call outs sooner, and be ‘over-prepared’, and then demobilize if necessary to insure that sufficient resources are available in advance of rapid escalation.

Regardless if your service territory is rural, multi-state, or condensed to a city, there are challenges in getting first responders, crews and materials deployed. Traffic, road closures, and poor conditions can bring a storm response to a crawl. Leveraging the lead time before event impact, along with staging equipment and resources, can be a significant advantage for your customers. Staging resources in the right locations is especially valuable. Critical infrastructure such as 911 call centers, hospitals, water treatment pumping stations, radio and television stations are a response priority. Mutual aid agreements can be a game changer even in smaller events when geography is a challenge. It may be strategically and tactically better to consider how a neighboring utility or contractor firms might be able to assist you in some geographic areas. Could you place materials, park trucks or trailers, or stage equipment at their locations before the season, or even before the event?

Preparation Schedule and Resource Groups

Preparing for events or storms often gets compartmentalized into the weeks and months just before the ‘typical’ season starts. There is a host of last minute, abbreviated, and inconvenient meetings and training presentations that do little more than fill a checkbox on the list with a checkmark. Sometimes the first storm is the preparation, and consistency isn’t even on the table for consideration.

TIP: Preparation for the next season should begin the day after the previous season ends.

Rigor is required to create consistent event responses, and procrastination is the enemy. Storm profile data and debriefs from previous year post-incident critiques is critical to preparations.

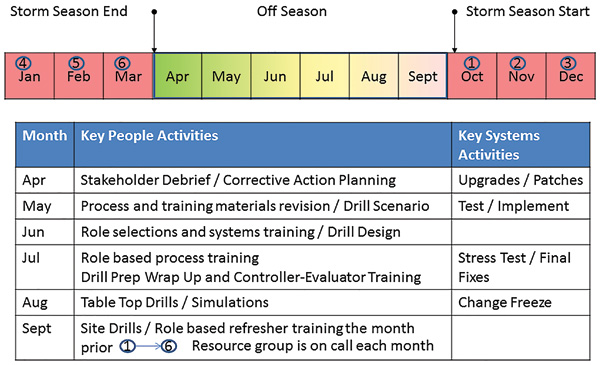

Figure 1 shows an example preparation schedule and activities. In this example, the storm season begins in October and ends April 1st. The people and system activities indicated are aligned around the people, process, and system components. The idea is to analyze the previous year storm profile data, gather the post incident critique information, and then drive corrective actions. Results from these efforts translate into a lot of very worthwhile work for several different groups. This work should occur in the off season and bring the best and most experienced resources together to collaborate and drive the corrective action effort.

Figure 1: Storm Preparation Schedule with Monthly People and System Activities

This preparation schedule utilizes the concept of resource groups, which are denoted by the numbers 1-6 in blue circles. These six groups represent role-based sets of responders for all necessary roles that would respond in the event of; System Operator, Load Analyst, Wire Guard-Make Safe, 911 Coordinator, Damage Assessor, Vegetation Management, Dispatcher, Materials Management, General Foreman, Operations Supervisor, and Storm/Emergency Management. If there is an event in October, resource group 1 responds and if in November, resource group 2 responds.

This resource group approach improves resource allocation and training. Group 1 should be made up of the best and most experienced storm response resources, and should be heavily involved in the off-season preparation efforts. Any new or inexperienced resources are assigned to groups 2-5. If there is an October event, new resources should be expected to respond with group 1 for a callout. This model provides an opportunity for new resources to work, learn, and practice with experienced resources in a real event. Resources in group 1 can be asked to help other groups in the ensuing months if those groups are called out.

Resource groups allow just in time delivery of refresher training such that it is scheduled just prior to the on call month for a resource group. For example, refresher training for group 5 could be in January. Finally, resource groups provide a ‘succession plan’ for large events. In a multi-day event, having a resource plan built in can be very helpful to keep productivity high.

Training and Simulation

Training of storm response staff is required due to turnover in operating staff, with more experienced operators retiring and being replaced by less experienced personnel. However, even the most senior distribution system operators require significant training on new technologies and operating requirements.

Training simulators, which provide interactive simulation of power system operations under normal circumstances and contingencies, can prepare the response team to meet these challenges. Training simulators shorten the time needed to train up new candidate operators and reduce time spent by senior operators supporting these training activities. Interactive simulators provide a realistic training environment where learners can practice and replay “what if” scenarios.

Foundational Training

Foundational system training should be a primary consideration for new resources. There is also a need for foundational ‘event or storm’ training that orients new resources to the big picture. If there are a large number of new resources or a significant change in systems or process then, more time and resources may be needed to update training materials and deliver the necessary training.

Role-Based Training

New and existing resources with a solid foundation need to learn the event work processes. There must be time to create or update training materials. Training is role-based, which means every role should know their responsibilities and how to perform the tasks they will execute during the event. Role-based training should be hands-on training; process based, with realistic simulated events, delivered by the best and most experienced resources.

Small Group Simulations, Role Plays, and Drills

When every role has been trained, then small (functional) group simulations that include role play commence. These small group simulations allow responders to work together, build confidence, open lines of communication and create a ‘response team.’ These small group drills should validate the role-based training and provide an opportunity for practicing the event workflows between roles in a functional area. This effort gets led by the best and most experienced resources for each role.

Utilities often miss detailed small group storm training. Training should occur in stages and include role play simulations within each work group as well as individual training based upon the character actions required. For example, Damage Assessors can practice documenting and packaging equipment damage assessments and hand off this information to crew managers. Crew managers can prioritize work and resource assignments and communicate with crews. In addition, 911 Coordinators can interact with system operators to prioritize public safety responses. Simulation role play validates the processes, role requirements, and training. Each simulated role play shall include an evaluation component. The evaluation process is essential to ensuring that training requirements and work processes get implemented, and any corrective actions are captured.

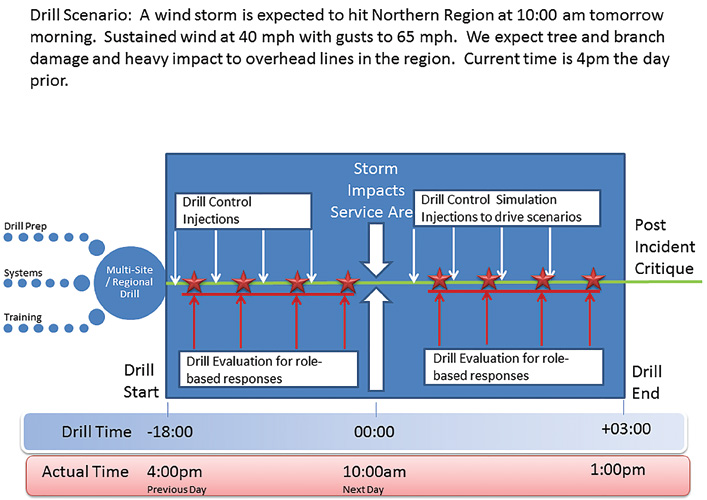

In Figure 2, the planning activities lead to a drill scenario that has control injections and role-based evaluations prior to the storm impacting the service area, and through the escalation. This requirement is critical to role play and practice of the ‘pre-impact’ actions as the storm scenario approaches and as the scenario progresses through escalation.

Figure 2: Training Simulation Timeline with Control Injections and Role-Based Evaluations

Utilizing a script editor allows simulated injections, driving a build up for limited outages and gradual progression of the intensity to drive storm response. Simulations should progress from the point prior to outages being received in system operations and progress through rapid escalation.

During the initial stages of the storm, pockets of small outages can be injected through the script to drive the response by the participating roles. During the initial start-up of a drill, invoke the response processes slowly and evaluate key decisions.

TIP: Practicing slowly during the beginning of the drill helps prevent overreaction and allows the users to build proficiency in implementing the storm processes.

As the storm simulation escalates, the role players should then begin making correct decisions based upon practice processes. During this portion of the role play, decisions should be supported by defined rules and time durations based on storm escalation. At key decision points, the utility must be proactive rather than reactive in setting up storm support personnel.

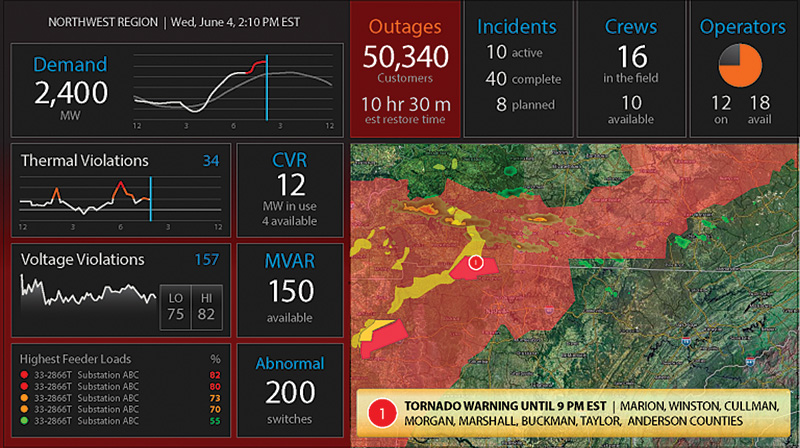

Before the storm escalates to peak, resource decisions must be made, and key players in support roles must be in place. Using system overviews and dashboards during simulation drills at all levels helps drive situational awareness that leads to making informed decisions (See Figure 3).

Figure 3: Overview Dashboard Displays Impact of Storm System

During the evaluation phase of the small group training, it is key for subject matter experts to validate the work process that occurs before and during a storm. By gradually working through this progression, weaknesses can be identified and practiced.

Multi-Site Exercises and Drill Scenarios

When small groups get experience and practice performing in response roles, the stage is set for a more comprehensive practice in the form of a multi-site drill or exercise. The multi-site component of this process provides an opportunity to align the response from a geographic perspective. For example, multiple service areas are hit by the event and coordination of the response and allocation of resources is across a broader area and involves more communication traffic and logistics. Often, the utility works to reduce the impact of the event to smaller areas and ends up leaving the region or area to fend for themselves during the winding down period of the event. One goal in this process is to drive the regional sites to consider supporting the hardest hit areas when they can do so. Multi-site or regional responses can focus on local geography and then augment the efforts of adjacent or hardest hit areas. This type of design in drills and exercises builds collaboration and customer focus that can be a game changer. The ability to on-board additional help in a given area takes practice. Sub-dividing a geographic region to enable on-boarding of additional responders is the goal and practicing this behavior can make a big difference to your customers.

Drill preparation for the next season also needs to occur in the off season. Again, knowing the shortcomings of the previous year and changes in systems or process is very important. Creating an over-arching drill scenario with detailed objectives designed to assess capabilities and improvements in areas of weakness is valuable. The scenario, drill timeline, goals, and objectives by role, and the timing are all part of the drill and exercise preparation. The drill and exercise process evaluates capability and identifies improvement areas. Multi-site drills and exercises utilizing simulation role play provide an opportunity to scale the response and re-allocate resources across the business based on priorities, outage duration or the amount and type of damage.

System Stress Testing

Knowing if changes, upgrades or new systems are capable of ingesting the volume of incidents and the number of users during a high volume event often gets looked over. Stress testing for high volume is a must before drills or exercises for high volume are scheduled and exercised. Communication systems should be stress tested in parallel to the high volume. Be sure to consider back-up plans for communications failures during preparation activities and test as part of the exercise process. The drill or exercise scenario can be designed to evaluate back-up plans for system failures.

SUMMARY

Storm preparedness starts from the utility leaders taking ownership of the planning and preparation process and involves year-round effort from all storm response team players. Storm simulation technology improves success by enabling the utility to conduct realistic emergency preparedness drills, preparing the total workforce to meet storm challenges.

About the Authors

Bruce Bjorklund is the Lead IDMS Technical Trainer and Change Management Manager at Alstom Grid. He has over 25 years of experience in the electrical utility industry including tenures with Puget Sound Energy, Lone Peak Utility and Southern California Edison. His background also includes serving as a high school teacher and coach, Bruce has extensive experience in system operations and with OMS, DMS and GIS systems. In the past 4 years, he has interviewed and/or worked with over 14 utilities. He holds a BS in Environmental Studies and is certified in Prosci Change Management.

Bruce Bjorklund is the Lead IDMS Technical Trainer and Change Management Manager at Alstom Grid. He has over 25 years of experience in the electrical utility industry including tenures with Puget Sound Energy, Lone Peak Utility and Southern California Edison. His background also includes serving as a high school teacher and coach, Bruce has extensive experience in system operations and with OMS, DMS and GIS systems. In the past 4 years, he has interviewed and/or worked with over 14 utilities. He holds a BS in Environmental Studies and is certified in Prosci Change Management.

Rich Cummings is President of Level Four Solutions Group, Inc. (L4SG). L4SG works with utility customers in the operations, construction, and maintenance to create and deploy custom training solutions such as e-learning, instructor-led training, on-thejob training for new employees and veteran employees. L4SG creates solutions that are business and need-based, working with subject matter experts and stakeholders to improve operations during blue sky and high volume operations. Rich has 20 years of experience in training and electric system operations. His background includes tenures with the Salt River Project and working with numerous utilities for GE Energy and L4SG.

Rich Cummings is President of Level Four Solutions Group, Inc. (L4SG). L4SG works with utility customers in the operations, construction, and maintenance to create and deploy custom training solutions such as e-learning, instructor-led training, on-thejob training for new employees and veteran employees. L4SG creates solutions that are business and need-based, working with subject matter experts and stakeholders to improve operations during blue sky and high volume operations. Rich has 20 years of experience in training and electric system operations. His background includes tenures with the Salt River Project and working with numerous utilities for GE Energy and L4SG.