If Smart Grid 1.0 was focused on installing the automated meter reading (AMI) infrastructure, Smart Grid 2.0 is all about the products and services that are imagined, developed and marketed to consumers, changing the traditional relationship between utilities and their customers. Utilities will become more customer-centric and actively engage and empower their customers with more information about their energy usage, the actual cost of that energy and new tools to better manage their consumption. But what if instead of utilities leading this transformation, it’s already underway outside of the traditional utility ecosystem, leaving unrealized value on the table for utilities and consumers and actually distancing utilities from their customers instead of bringing them closer?

The reasons for utilities to transition to Smart Grid offers are many, complex and often interrelated. They include:

- Increasing the percentage of renewable resources;

- Increasing cost of centralized generation;

- High cost of meeting peak demands;

- Cost of replacing an aging infrastructure that requires significant upgrades; and,

- Managing the impact of new technologies such as distributed generation and electric vehicles.

These are multi-dimensional issues that require a well thought out transition involving the utility, the regulators and consumers. However, what if this transition is already underway and being driven by parties from outside this well established paradigm? What if consumers were actively engaged by new technology and offers that appeal to their needs in ways that don’t align with broader industry goals? How might these third-party services impact or erode demand with little visibility or control by utilities left to react rather than act? This has happened before in many different industries and may already be happening in the energy ecosystem.

Two of the best examples of this change happening outside of the utility purview are Nest and Solar City.

Many utilities have offered some form of thermostat or load control program to tie the consumer into programs such as demand response (DR), a critical peak pricing program (CPP), or energy efficiency campaigns. The utility (or third-party aggregator) plays a very important role in this program and incorporates this additional information and control into the supply-side of the business to drive efficiencies and share the resulting value.

For example, during a DR event, when the cost of power is at its highest, the utility either cycles off the AC or adjusts the thermostat, resulting in real savings. A portion of this savings is passed to the consumer usually in the form of a rebate or bill credit. The utility has visibility into the end load and makes decisions accordingly.

However, what if innovation occurs outside of this ecosystem? One of the more interesting energy products to come out in a long time that supports such a case is the Nest, a “learning” thermostat developed by former Apple employees that uses a combination of algorithms, motion detectors, internet connectivity, a web portal and an easy-to-use interface. The value proposition to a consumer is very straightforward: it is easy to use, will save you money, looks good on your wall and keeps you comfortable.

If Nest is successful, this could result in a significant number of higher usage customers (i.e., those with the income and usage to save enough to payback the initial cost of the Nest – think segmentation!). This would allow customers who dramatically change their usage and load profile to do so at will, and with the only indication given to utilities being lower usage and reduced bills.

This usage isn’t tied into any of the EE or DR programs, leaving potential operational benefits and value on the table for all parties. The consumer interfaces with a specialized website, a downloadable iPhone app and a Nest thermostat, but not the utility. Nest has innovated around the in-home consumer energy experience and changed the energy relationship. I should tell you that I am a Nest customer myself, and in the first month with the device, I saved approximately 20% on my heating bill.

Another example of this change is Solar City and its residential photovoltaic (PV) program. Again, a very straightforward value proposition: save money, combined with an innovative business model that removes the upfront cost barrier. This has led to significant customer engagement and surging subscribers. While there are certainly regulatory incentives that facilitated this market (e.g., feed-in tariffs and subsidies), it’s clear there has been traction for this offer.

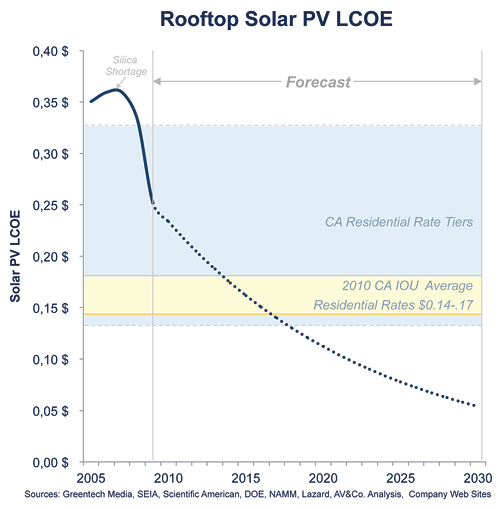

As with Nest, the consumer relationship is with a new player, Solar City. As rates continue to grow, residential PV becomes an economically viable alternative for more consumers, which drives scale and reduces cost. In turn, PV is economical for more customers – a very typical technology adoption cycle. In some states, such as California, this trend is magnified by high rates, high subsidies, feed-in tariffs, and an excellent solar resource (i.e., lots of sun). Therefore, the kWh cost of these models is becoming more economical. (See chart)

Consumers are making the decision based upon what is best for them, forcing the established utility ecosystem to react. Mass adoption of PVs certainly brings with it many benefits, but there are also implications to the established ecosystem. For example, high-use customers may be the most likely to move to this form of alternative power, reducing the aggregate consumption base over which the cost of the T&D infrastructure is levelized, driving up rates for those still dependent on the traditional centralized power system. As with Nest, a portion of the consumer-energy relationship has evolved.

These issues are not unique to the energy industry. We have seen this type of change occur in another wire-centric industry, local voice. The incumbent provider – the phone company – had a local monopoly on its version of the “distribution grid”, the local copper plant. Yet new technologies such as wireless proved to be incredibly disruptive to the historical model. Over a very short time, we saw a dramatic shift in the number of copper wires required by consumers. In this case, a new network, driven by technology and consumer preferences to be mobile, was literally created out of thin air. Is Distributed Generation (DG) – for which PV is one form – that “next” network?

We have also seen attempts by the wireless industry to control the customer experience on “their network” with modest success with new consumer services such as ring tones, games and music. Because there was limited competition, this consumer-mobile content relationship evolved slowly. This was not because consumers didn’t want the services, but rather because they were not being provided in a way that consumers wanted. Along came Apple and its competing ecosystem of iTunes and the iPhone. Now almost all mobile digital content is delivered through third parties like Apple, the Android app store, the Kindle store, the Nook and others.

The challenge for the existing ecosystem is not how do we drive this change. Rather, it is how do we create an environment that enables change so that consumers get what they want, and delivered in a way that contributes to solving the real world problems that the industry is facing.

We need to allow more market forces into the ecosystem, but in a way that protects the historical utility investments and consumers.

Conclusions

If we want PV and DG, we need to move away from a variable cost recovery mechanism (kWh) for a fixed asset – that is, the transmission and distribution grid – perhaps a fixed fee for connectivity that varies on total potential load could work.

If we want to avoid the lost value of utility disaggregation in the home, we need to make the meter data available to those parties the consumer selects and let creativity and innovation flourish in the home while still providing the visibility to the utility to maximize the value on the supply side as well as the demand side.

About the Author

Matt Dinsmore is a director at Altman Vilandrie & Company and leads the firm’s Energy & Clean Tech practice. He has over 18 years of experience building, growing and advising companies in the energy, telecommunications and technology industries. Matt has extensive experience in customer engagement, technology evaluations, demand assessments, new product development, business case development and go-to-market planning. Matt is a frequent speaker on Clean Tech and the Smart Grid at industry events, was the primary author on the Smart Grid Consumer Collaborative Excellence in Customer Engagement Report, and served on the Board of Advisors for Xcel Energy’s Smart Grid City in Boulder, Colorado. Matt holds an M.B.A. from the University of Chicago Booth School of Business and a B.S.B.A from Washington University in St. Louis.

Matt Dinsmore is a director at Altman Vilandrie & Company and leads the firm’s Energy & Clean Tech practice. He has over 18 years of experience building, growing and advising companies in the energy, telecommunications and technology industries. Matt has extensive experience in customer engagement, technology evaluations, demand assessments, new product development, business case development and go-to-market planning. Matt is a frequent speaker on Clean Tech and the Smart Grid at industry events, was the primary author on the Smart Grid Consumer Collaborative Excellence in Customer Engagement Report, and served on the Board of Advisors for Xcel Energy’s Smart Grid City in Boulder, Colorado. Matt holds an M.B.A. from the University of Chicago Booth School of Business and a B.S.B.A from Washington University in St. Louis.