Early on July 30 of this year, some 370 million people were dropped in the dark when an inter-connect substation near Agra, home of the Taj Mahal, tripped causing the automatic shutdown of all power plants in the Northern region. Fortunately, Delhi’s international airport, hospitals, police stations, large-scale commercial and industrial power users, and higher-end homes were okay with backup generators. Not so fortunate were the everyday people who were stuck with no light, no heat, and no public transport. Traffic jams were a nightmare with no traffic signals; rail commuters were stuck in dead electric trains, and countless small businesses had to close.

The following day, the eastern and north eastern power grids went dark. The 20-state blackout saw somewhere between 620 million and 680 million people – about half of India’s population – trapped with no power. This time, some critical operations also lost power. The calamity was caused by a few states in the northern grid that overdrew power beyond their permissible limits, ignoring warnings from the dispatch centre and regulatory body to stop the practice. The three biggest culprit states overdrew in June by an average of 29.8 million units per day and then overdrew on average 15.1 million units each day from July 10 to 16.

What’s troubling is that these states have refused to install under frequency relays (UFRs) for automatic demand management programs. They opted instead to run the risk of a huge failure and it has cost them dearly. According to local authorities, overdraw has been much higher in the past as well and this continued abuse of grid discipline over time has systematically weakened the system.

As automatic relays shut down the most overloaded transmission lines and generators, power surged around the rest of the network taking increasingly unpredictable pathways. As this unbalance sped through more and more of the system, an untenable number of emergency shutdowns occurred until the grid and power generation collapsed across the region. The fingers of blame didn’t stop pointing there. Around 56 per cent of India’s total power generation capacity is from coal and there was a shortfall of 88 tons of the stuff for that power sector for 2012 and 2013. Natural gas production has been falling off over the last few years leading to shortages for power plants.

“Today, India is caught in a vice between rapid commercial growth and intense energy demand, which are obviously related,” says Mark Cerasuolo. “The country now competes with China, Japan and South Korea to import fossil fuels, and recently has been contending with sanction-driven cutbacks on Iranian oil imports. The situation is at the point where inherent shortages of oil, gas and coal have ‘substantially contributed to a second year of slowing economic growth in India,’ as Vikas Bajaj reported in a NY Times article in April. Rahul Dhir, the head of Cairn India, Ltd., India’s largest private oil company, is quoted in early July as saying that ‘we are headed 100 miles an hour into a brick wall on energy security unless we do something radically different.’ This latest event proves his point.

“India is not unique in this; there are a number of rapidly developing countries that are bypassing the traditional infrastructure expansion models and leapfrogging into less centralized technology,” continued Cerasuolo. “One case in point is telecommunications. The U.S. and much of the West had decades of wired networks in place before wireless became the default, whereas India and other countries are sidestepping this wired stage, and moving straight to wireless. Consequently these countries rely on decentralized power generation to accomplish this because there’s no grid near the remote stations. Renewable power has seen a lot of growth in India for this reason, since converting solar or other generated energy onsite is essential to powering these emerging wireless networks.

“At the grid level, the same thing applies: the country has a patchwork of local electricity grids, which suffer from instability and inconsistency and are exacerbated by extremely high fuel prices. This has spurred growth in renewable energy highly accessible to India, such as solar. When paired with backup systems, renewable energy provides more reliability. This latest historic outage event shows how important it is for India to achieve as much independence as possible from fossil fuels and move toward practical, sustainable onsite generation.”

All of this was not lost on the forward thinking of Malankara Plantations Ltd. in Kerala, India when they elected to use OutBack Power for the necessary tools and advanced photovoltaic (PV) technology to divorce the business from the grid and get out from under their on-going electrical power challenges that exist because of the nature of the electricity system in their country.

The building complex was originally connected to a private power grid owned by a local maharajah and in 1950 was taken over by the Kerala Electricity Board. The complex was slated to move off grid because it had some backup generation. In order to be free of the grid no less than a unique and ambitious engineered solution was required that would make absolutely no alterations or disturbances to the original structure.

“The idea of setting up a solar power plant was a long-standing ambition,” says J.K. Thomas. “When we could not get the one megawatt project under the Ministry of New & Renewable Energy (MNRE) Scheme, we decided to put up a 25 kilowatt (kW) PV system for our office complex for which we have used OutBack inverters and charge controllers.”

The compound houses an 86-year old structure that is classified as ‘heritage’ so a strict preservation policy is in place, which is mandated by the state. The plantation is located in Kottayam district in southwestern India and the tropical climate means daily temperatures in March, April and May consistently exceed 86 degrees Fahrenheit (30 degrees Centigrade). Intense rains accompanied by severe lightning occur during this time and humidity is regularly 90 per cent and higher. This type of weather takes a real toll on people and equipment.

The new system is powered by a three-phase 27 kW array of nine OutBack GVX 3048 off-grid inverters. The arrays consist of 25 kW modules in space frames, comprised of thin-film PV elements. Grid-interactive PV inverter systems solve problems that have plagued both off-grid and grid-tied applications, providing integrators with previously unavailable flexibility and reliability for high-end deployments.

“When the project was completed by Team Sustain we were proud to realize that we were one of the first office complexes in India to be fully solar powered, including 17 tons of air conditioning, all lights, fans, three motors and our three packeting machines,” Thomas continued. “It was more of a novelty than a financially viable operation when we installed it in January 2012. However, today India faces a huge power shortage and power failures and power cuts are a daily recurring problem to all energy consumers so we are really happy that we do not use any grid power and are fully insulated from power supply interruptions. With the tax concessions and other incentives provided by the government of India we hope to recover our capital cost within five years considering the ever increasing cost of power.”

Advanced power electronics that harness the elements for greener, cheaper power generation and delivery were ideal to meet the Malankara challenges. They are the products of choice for providing solutions in harsh environmental conditions where product reliability is paramount. To this end, off-grid inverters with battery back-up, grid-tie inverters with battery back-up, maximum power point tracking (MPPT) charge controllers, communications/network products, and integration hardware is ideally suited. Inverters that deliver pure sine wave power to residential and commercial entities along with rugged and reliable conversion electronics for battery storage are fast becoming one of the key go-to technologies that will help define the use of renewable energy in the first third of this century

Malankara Plantations Ltd. – A true commitment to using renewable energy

Following the installation the complex was disconnected from the grid and continues to function solely on self-generated solar power. It is one of the first Net-Zero office complexes and is among the first Net-Zero Energy buildings in India, has a five-star energy efficiency rating, and has the capability of selling excess electricity to the grid.

“In fact, we are now negotiating with the Kerala State Electricity Board (KSEB) and Kerala State Electricity Regulatory Commission (KSERC) for evacuating our excess power to the grid which we hope will become a reality by the end of this year. If so we will be the first to supply solar energy to the grid in Kerala,” remarked Mr. Thomas.

The success of this installation has generated a lot of interest and has resulted in several inquiries from other plantations in the region. The Malankara project has shown that the potential is there to help countries like India tackle its electrical power problems. Hospitals, factories, government buildings, and residential blocks could generate their own power and scrub off a portion of their draw from the grid during peak demand. These systems could be self-reliant if solar was added to the generation mix supported by a demand response program, and energy storage systems.

It was quite telling when the media started calling for the installation and use of micro grids – pockets of power and consumption that can look after themselves and also have the ability to bail out the main grid when it’s under pressure – and solar power.

The question now before the people is: Could smart grid technologies help solve the problems that caused these blackouts?

It’s no secret that India’s grid is in a terrible state. It consistently loses money and is plagued by daily power outages, and consistent power losses in the 20 to 50 per cent range due to technical and non-technical power losses such as inefficiency and theft. The country’s fast-growing technology sector has had to come up with its own power. Unfortunately, most of that backup power comes from inefficient diesel generators that pollute the neighbourhoods in which they run.

As backup power technologies continue to advance, they could be the ticket to unlocking India’s smart grid potential, at least in the short term. The future looks strong for micro grids.

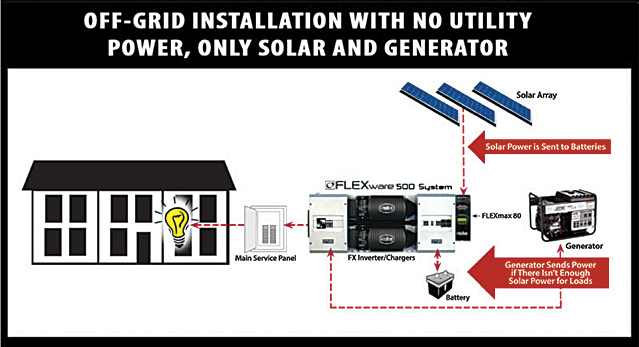

Typical configuration – straightforward, reliable, expandable, and sustainable

(click to enlarge)

Looking to the future, India’s potential to become the next big solar power market is in question. Its high-voltage grid is relatively stable, making large-scale solar integration a viable proposition. However, the low-voltage and medium-voltage grids are in rough shape. The country is coming on as a hotbed for off-grid solar power and the potential for installing in excess of 1 gigawatt per year by 2016 is in the offing. Given that more than a third of India lacks electricity from any source, rural micropower will offer huge prospects and a true need for rugged, reliable, and cost-effective solutions.

About the contributors

Mark Cerasuolo manages marketing at OutBack Power, a designer and manufacturer of balance-of-system components for renewable and other energy applications. Previously, he held senior marketing roles at Leviton Manufacturing, Harman International and Bose Corporation, and was active in the Consumer Electronics Association (CEA).

Mark Cerasuolo manages marketing at OutBack Power, a designer and manufacturer of balance-of-system components for renewable and other energy applications. Previously, he held senior marketing roles at Leviton Manufacturing, Harman International and Bose Corporation, and was active in the Consumer Electronics Association (CEA).

Mr. J. K. Thomas joined Malankara Plantations Ltd. In 1980 and is currently managing director. He received a Bachelor’s degree in Economics in 1976 and three years later was awarded a Bachelor of Law degree. In 1982 Mr. Thomas completed the Management Education Program (MEP) at the Indian Institute of Management, Ahamedabad (IIMA). He is active in the Plantation industry and several social services organizations in Kottayam.

Mr. J. K. Thomas joined Malankara Plantations Ltd. In 1980 and is currently managing director. He received a Bachelor’s degree in Economics in 1976 and three years later was awarded a Bachelor of Law degree. In 1982 Mr. Thomas completed the Management Education Program (MEP) at the Indian Institute of Management, Ahamedabad (IIMA). He is active in the Plantation industry and several social services organizations in Kottayam.