A major storm has hit the area. Thousands, maybe even tens of thousands, are without electricity. The utility company must resolve the outage emergency as soon as possible – a large part of which involves crew-care logistics, such as how many people will be required, how many crews, where they will be lodged, how and what they will be fed, how information will be communicated to them, and countless other tasks.

The ability to accomplish these diverse, complex tasks can literally make the difference between customers having or not having electricity for days; between having satisfied customers complimenting the utility on its effective response to the emergency or screaming bloody murder about what a mess it made of things.

So what are you going to do about it?

To find out the answers, Macrosoft, Inc. conducted a study among key personnel from utility companies around the country.

The survey was conducted during August 2014 using an online survey tool. Some 76 individuals participated, representing a broad spectrum of organizations across the country, including investor-owned as well as municipal utilities and cooperatives. Macrosoft asked a comprehensive range of questions about crew-care logistics, with the opportunity to answer both closed (pre-determined) and open-ended (free-form) questions.

Their responses ranged from predictable, to surprising, to remarkable.

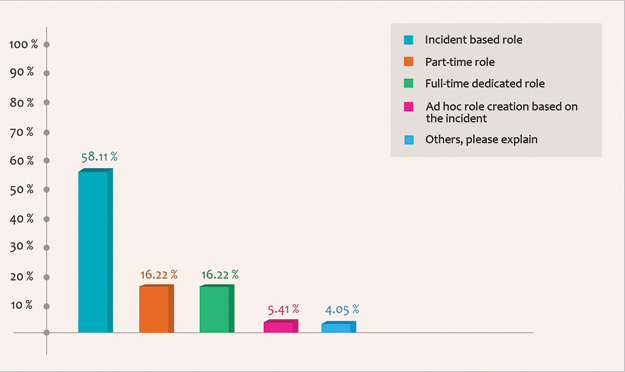

Let’s start with logistics preparedness during a blue-sky day prior to a large-scale incident. There is no doubt that utilities are cognizant of how important logistics is. Virtually all respondents (96%) say crew-care logistics is “very important” to the emergency management process. But only about one-third of the companies have personnel responsible for crew-care logistics on a full-time or even part-time basis. Remarkably, even companies which have handled 10 or more incidents over the past year are deficient in this area with only 29% having full-time and 7% or part-time personnel.

This means that, for each incident, the people entrusted with this key function are literally a ‘Hobson’s choice.’ Whoever is available, regardless of experience or knowledgeability level is engaged in logistics planning rather than personnel with crew-care management experience.

Regarding how the operations themselves are handled, about half of all study participants tell us their companies centralize operations, resources and logistics in one place, with the rest at separate locations. Not surprisingly, the nature and scope of each individual incident determines most companies’ decisions regarding whether to centralize or disperse these functions.

In one respondent’s words:

“We use ICS for significant response, so depending on how big a restoration effort we may have tactical leaders on the ground with the crews as well as a full ICS team at our corporate EOC – including all command and general staff”

LOGISTICS CHALLENGES

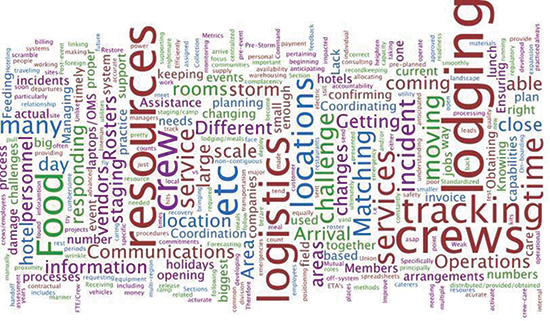

When asked what the single biggest challenge of crew logistics is, the two most frequent mentions are lodging and food.

Biggest Challenge Crew-Care/Logistics Processes

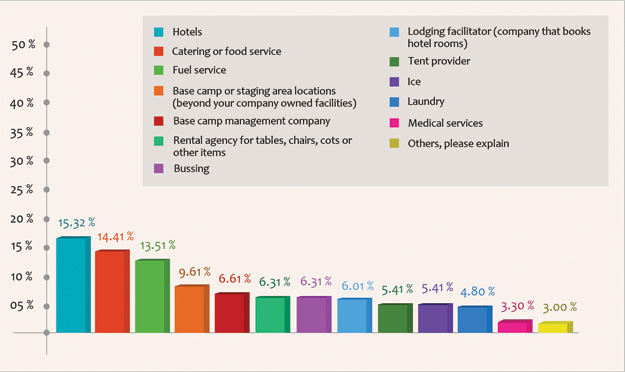

Yet, despite their importance, a majority of utility companies do not have standing contracts with any companies or organizations which provide these essential crew care services.

Surprisingly, only 21 percent indicate they have contracts with hotels. Even fewer (19%) have contracts with catering/food services. Even for fuel, only 19 percent have contracts.

And, inexplicably, companies which handled the greatest number of incidents in the past year are less likely to have such contracts than companies which handle the fewest.

Standing Contracts

Beyond these mainstays, most other challenges again relate to the unpredictability of each individual incident, and that circumstances during an incident can change while it is in progress, thus necessitating corresponding changes in crew logistics ‘on the fly.’

This clearly underscores the need for logistics planning in advance and the development of immediate, comprehensive communications capabilities which, as information becomes available about the incident and what is needed to handle it enables managerial personnel to get everyone on the same page as quickly as possible.

LODGING

Looking at lodging specifically, there is no clear direction to how it is accomplished: about one-third of study participants say hotel rooms are typically secured and managed locally, one-third say this is done from a central location and one-third say it varies – depending on the size and scope of individual incidents. The biggest bottleneck/issue with lodging is the most basic one; finding and booking enough hotel rooms for crew members.

Another is room distribution. As one participant notes:

“Occasionally, when the hotels give your rooms to other groups representing the utility, or accidentally (do so), it creates havoc and distractions trying to retain more rooms”

Finding rooms in proximity to the incident remains challenging and, interestingly, the practical matter of physically getting room keys to crew members can be complicated.

If, as sometimes happens, hotel accommodations are not available, companies very much prefer that hard-shell buildings be secured for crew personnel. Two-thirds say they are either ‘preferred’ or at least ‘acceptable’ Mobile sleep trailers are well behind, but still ‘acceptable’ to about half, while tents are emphatically disliked.

MEALS

For lunch the one meal certain to be needed during the work day, respondents strongly prefer that box/bag lunches be provided to crew members in the morning, with some feeling it would be better to deliver the meal to crews in the field (possibly so crews can have a hot lunch).

Loss of work time is the single biggest issue when it comes to feeding crews – which is why box lunches are seen as superior to buffet lunches or restaurant meals, both of which require time away from the actual work site.

BASE CAMPS

Although opening a base camp presents significant logistical problems, the ‘good news’ is that they are not needed very frequently. About half the study participants tell us they have not had to open one in the past five years, and about four in five (78%) have done so less than once a year during this period.

But when base camps are needed, respondents are very clear about the components they consider most important, including:

- Site size/capacity (97% rate it ‘very important’)

- Location within the service territory (93%)

- Entrance/exit accessibility (89%)

- Security (82%)

Though 82 percent rate security ‘very important’ (and 98% rate it ‘very’ or ‘somewhat’ important), a staggering 93 percent of study participants tell us their companies do not issue ID cards, wrist bands, or other such credentials. This obviously maximizes the risk that unwanted personnel can get into the base camp, or have access to work sites. There is a major disconnect between the perceived importance of security and company follow-through.

HOW TO MANAGE CREW-CARE LOGISTICS

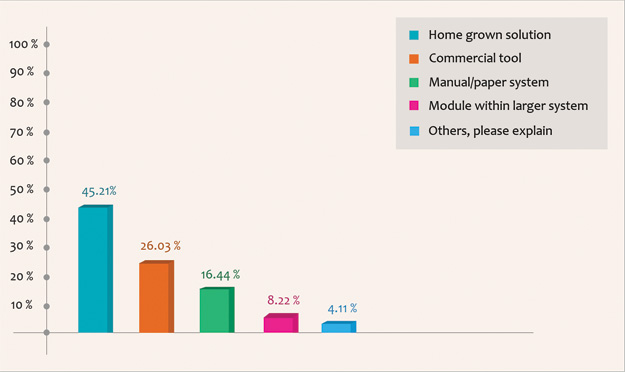

The single most-used method/process for managing crew-care logistics during a large-scale emergency restoration involves a variety of ‘home-grown’ solutions, such as SharePoint, spreadsheets, etc. While certainly not specific to utility outages, at least they are progressed from the 16 percent who are still using whiteboards and paper forms.

About one fourth (26%) use software solutions to quickly handle most crew-care logistical issues. 36 percent of the participating companies which handled 10 or more incidents over the past year are most likely to have such software.

Methods for Managing Crew-Care/Logistics

Communications-wise, crew-care/logistics instructions are mostly passed along by phone (36%) or email (25%), with text messaging well behind at 12 percent.

Given the companies’ low percentage of software usage; it is hardly surprising that study participants are dissatisfied with their companies’ crew-care logistics methods. Only one-third (34%) of study participants are ’very satisfied.’

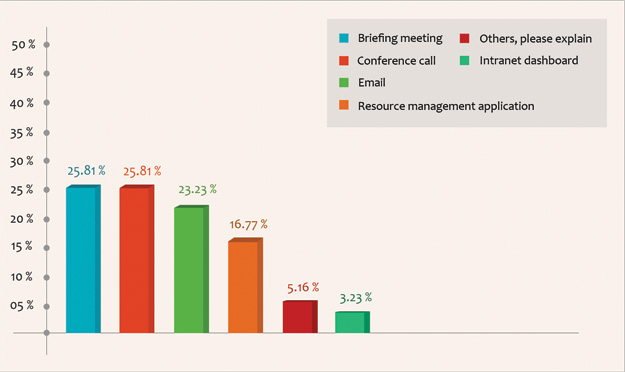

Communication Methods

This is clearly reflected by their suggestions regarding how logistics management communication be improved. Here is just a partial sampling:

“Reduction in paper based communication of information to work force”

“Use electronic communication, consistently across the entire organization”

“Easier to use web tool, more intuitive, easier to navigate, easier to manage...”

“A single software program that all the company would use; this way info in support and numbers would be real time”

“Integrated, automated”

“A computer-based system that could share date from multiple points”

“We need a tool in which all functional groups are able to access”

“Provide a tool that would allow ease of tracking crews and equipment”

CONCLUSIONS

It would be hard to overstate the importance of excellent logistics for crew-care. The most important elements of crew-care necessities – food, lodging, and transportation to/from the outage areas are self-evident.

Our study shows that the systems in place to manage crew-care logistics are all too often mired in the past, which obviously has negative implications on quick power restoration.

It is easy to see why problems can arise, given the way this key component of incident resolution is treated. Less than one third of the companies in this study have personnel responsible for crew-care logistics on a full-time or part-time basis. Among companies which handle 10 or more emergency operations a year, only 36 percent have such personnel. Instead, they rely on assigning non-dedicated personnel to each outage, on an incident-by-incident basis.

As for coordinating lodging, food, fuel, transportation to and from work sites, creation of a base camp, monitoring/communicating changes in what has to be done as the situation evolves, and the countless other components of emergency outage incidents, most companies lag far behind the curve. This maximizes the potential for problems to arise, and for little problems to grow into big ones.

That is why it is inexplicable that, in an age of technology, only 26 percent of the people surveyed in this study use dedicated software to manage and coordinate crew-care logistics. Even among companies which handle 10, 20 or more incidents a year, only 36 percent do so with 16 percent still using white-boards and notepads.

Over 200 years ago Napoleon said an “Army Marches on its Stomach.” The same can be said for restoration crews today. If you expect excellent quality work under tight dead-lines from a busy crew of lineman, be sure your company has systems and processes in place to feed, lodge and care for the critical people who are restoring the power.

About the Author

John Kullmann is Vice President of Marketing and Sales at Macrosoft, a New Jersey Technology company. With more than twenty years’ experience, John is a recognized expert in business development efforts for professional services firms. He is responsible for expanding Macrosoft from its traditional roots as a leading software development and system implementation company into an equally accomplished provider of packaged technology products.

John Kullmann is Vice President of Marketing and Sales at Macrosoft, a New Jersey Technology company. With more than twenty years’ experience, John is a recognized expert in business development efforts for professional services firms. He is responsible for expanding Macrosoft from its traditional roots as a leading software development and system implementation company into an equally accomplished provider of packaged technology products.