While the concept of Automatic Meter Reading (AMR) is not new, many factors have created a doubledigit growth rate among electric utilities. Tracing the roots of the mass scale AMR systems, however electric utilities were not the initial adopters of this technology. The initial efforts and the creation of this industry was lead by water utilities, with the Hackensack Water Utility being the first to deploy technology system-wide to read meters. Likewise, it was a handful of passionate people involved with this effort, guided by Donald Schlenger of Cognyst Consulting, who shared the vision of promoting standards and education that lead to the formation of the Automatic Meter Reading Association (AMRA).

After nearly two decades of existence, the AMRA is the only not-for-profit membership association dedicated to promoting advanced metering, data management and communications technologies worldwide. It serves as an information resource to enable users and suppliers to stay informed about emerging technologies and products, equipment compatibility, industry standards, relevant legislation and regulatory initiatives, AMR trials and deployments.

Within the business model for justification of AMR, there are common drivers, such as the reduction of estimated readings, increasing the accuracy of readings, labor and other cost reductions that AMR brings that form the core baseline economic factors. Yet, some unique need areas within the electric utility have created a focused effort to incorporate AMR as a critical element of a business redefinition process.

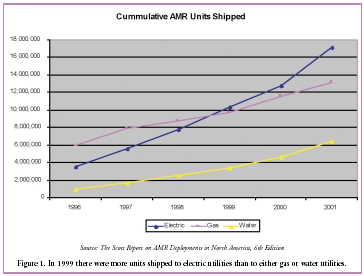

According to the Scott Report on AMR Deployments in North America, the total number of AMR annual shipments to electric utilities rose significantly in 2001. This is shown graphically in Figure 1.

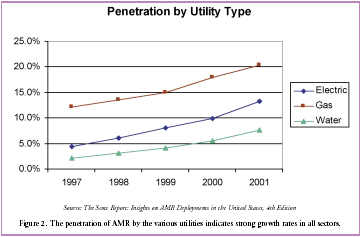

While the absolute number of units indicate more shipments to electric utilities, there is a higher percentage of the gas population that has AMR. See Figure 2.

What are some of the key drivers that are creating this growing interest and acceptance of AMR in electric utilities? Some of these value added features beyond monthly revenue reading include a renewed interest in Demand Side Management (DSM), new tariff structures for residential time of use, web presentment of energy information, and a focus on Customer Relationship Management (CRM)

Demand Side Management

Historically, in the height of the oil-embargo during the 1980’s, there was a significant effort to develop energy conservation. Public utility commissions, government and utilities alike collaborated on initiatives to manage power production and distribution to reduce our dependence on foreign oil.

Yet the DSM days of two decades ago have not totally waned, according to the EIA: “In 2000, 962 electric utilities report having demandside management (DSM) programs. Of these, 516 are classified as large, and 446 are classified as small utilities. This is an increase of 114 utilities from 1999. DSM costs increased to 1.6 billion dollars from 1.4 billion dollars in 1999. Energy Savings for the 516 large electric utilities increased to 53.7 billion kilowatthours (kWh), 3.1 billion kWh more than in 1999. These energy savings represent 1.6 percent of annual electric sales of 3,413 billion kWh of reported sales to ultimate consumers in 2000. Actual peak load reductions for large utilities decreased in 2000 to 22,901 megawatts. Potential peak load reductions of 41,369 megawatts were a decrease of 2,201 from 1999. In 2000, incremental energy savings for large utilities were 3.3 billion kWh, incremental actual peak load reductions were 1,640 megawatts, and incremental potential peak load reductions were 3,162 megawatts.”

This renewed focus on DSM (Load Reduction, Peak Shaving, or Load Shifting) is not just to reduce our demand on oil but to help maintain a balance between supply and demand. While each of the initiatives had roots in the energy crisis, many of their results have direct applicability today.

Load Reduction – these initiatives drive the load curve down, lowering the overall consumption. Some of the results of this effort included the evolution of energy efficient appliances, improved lighting units, such as compact fluorescent and insulation/window programs. In 1992 the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) introduced ENERGY STAR as a voluntary labeling program designed to identify and promote energy-efficient products to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Later, in 1996, the EPA partnered with the US Department of Energy for particular product categories, such as computers, copiers, electronics and other consuming devices. Recently the EPA has extended the ENERGY STAR branding to commercial, industrial and residential properties.

According to information from ENERGY STAR, homes that bear the logo have been designed to achieve a 30% savings for heating, cooling and water heating when compared to standard construction practices. This equates to an annual energy savings of between $200 to $400 annually. According to the National Energy Policy Act of 2001, 4.8% of disposable family income is spent on energy

Peak Shaving – Since mass storage of electricity has not yet been perfected, capacity must be provided to support peak consumption and demand. With the advent of distributed generation capabilities, many large users are beginning to use these reserves to offset peak demand charges. To achieve accurate measurement of the utility supplied energy and self provided energy use, a majority of states in the US have rules that govern the use and permission of Net Metering.

According to US Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, “Net Metering allows the electric meters of customers with generating facilities to turn backwards when the generators are producing energy in excess of the customers’ demand, it enables customers to use their own generation to offset their consumption over a billing period. This offset means that customers receive retail prices for the excess electricity they generate. Without net metering, a second meter is usually installed to measure the electricity that flows back to the provider, with the provider purchasing the power at a rate much lower than the retail rate.

Net metering i s a low-cost, easilyadministered method to encourage customer investment in renewable energy technologies. It increases the value of the electricity produced by renewable generation and allows customers to “bank” their energy and use it a different time than it is produced giving customers more flexibility and allowing them to maximize the value of their production. Providers may also benefit from net metering programs because when customers

are producing electricity during peak periods, the system load factor is improved.”

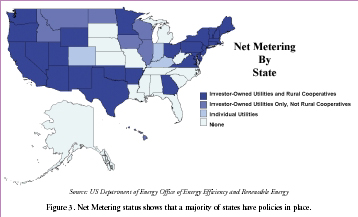

As of late summer 2002, thirty six (36) states had policies in place to deal with the concept of net metering. This is shown in Figure 3.

Load Shifting – While the concept of net metering allows the use of exisiting meters,it is expected that the impact of this initiative will be a need to upgrade meters and the communications between the utility and end user.

New tariff structures and services for residential customers

So much of our behavior is driven by time. From the morning alarm clock to the 6:18 am train, our life is oriented around time-based activities. There are many programs that have successful linked an economic benefits with a shift in time of use. For example:

On the New Jersey Transit northeast rail line serving New York City, the off-peak transit rail rate is 25% less if travel does not take place during the peak commuter period between 5:45 am and 10:00 am inbound and 4:00 pm to 8:00 pm outbound.

Travelers who pay cash at the tollbooths on the New Jersey Turnpike have a flat, time insensitive rate, based on distance traveled. E-Z Pass transponder travelers automatically participate in a time of use plan. Using this electronic tag, the toll rate is 12% less than the cash rate during the peak times of 7:00 am to 9:00 am and 4:30 pm to 6:30 pm weekdays. Users during the off peak period and realize a 20% discount.

On a typical cellular calling plan, calls placed from 9:00PM to 6:00 am Monday through Friday and from 9:00 pm Friday to 6:00 am Monday during the “Weekend and Evening” rate pay and are less than 50% less than the on-peak rates.

The overall consumer acceptance of a time of use incentive/penalty approach appears to be growing, especially when the ability to modify behavior can result in a tangible financial benefit. Yet, there has been little penetration of Electric Residential Time of Use in the United States.

In a recent study performed for a Fortune 100 firm, RJC-Consulting, LLC surveyed over 100 electric utilities covering the top 50 utilities that are investor owned (IOU’s) and at least one utility from each state to determine their current residential Time of Use (RTOU) program and the number of participants in these programs. Except for a few major initiatives, the percentage of customers currently participating in these programs, was less than 1%. A number of reasons for this lack of acceptance was cited in the report. They included: a lack of promotion of these on the part of the utility; the structure of the program itself, including the start-up costs, and cost spread between peak and off peak rates and the incremental cost of the TOU meter itself that was passed on directly to the consumer. All these factors contributed to the lack of incentive for consumers to justify a change from a flat rate to a TOU rate. Virtually all the programs evaluated did not give the customer any real-time indication or tangible dollar amount one could save by shifting load to an off peak time.

Energy efficiency comes into play often when individuals are making decisions about certain products. However, the energy consumption savings projected over the life of the product can confuse many consumers. This is especially true when they are forced to evaluate the future value of an investment they must make today with little information about their historical usage. Saving $15 a month on a new refrigerator must be compared to what is being spent today on the same appliance, and that information on an individual element is at best estimated or projected. The energy consumption sheets on products have a value that is similar to the estimated miles per gallon displayed on the specification sheet of a new vehicle. Actual results may vary based on individual consumer use habits.

Obviously, when the cost of energy is high, the trend would be that consumers would buy more efficient products. In a stable energy cost environment, unless there is a way to inform customers about the actual cost of the energy used by the device, the weight of the a higher efficiency choice argument may be minimal. In a volatile energy cost market, consumers need receive current electricity costs in order to make efficiency decisions or to make adjustments to their energy use to take advantage of any time of use service that is available.

Further, there are few devices that automatically modify their operational characteristics based on the actual time of day. When non time responsive loads are operated in a TOU environment, the load is averaged across the off-peak and on-peak rates. Often the higher cost of on-peak electricity masks any savings that may be realized during the off peak period. Therefore, consumers may not recognize the benefits of investing in technologies that operate or shift load to off-peak consumption periods or to ensure that the clock within the device is kept accurate.

The advanced services provided by more sophisticated metering systems can bridge this gap by providing both time sensitive energy use information to consumers and by being the gateway to network devices that measure, calculate and display energy costs. Often this is an element of an AMR system that is difficult to quantify in an economic model.

Information grade metering can complement revenue grade metering

While the growth of AMR for revenue metering is apparent, an underserved area of AMR in the information grade or submetering arena. Although once perceived as a threat to the metering department, these element monitoring devices and units are now gaining new respect.

Just as 15 minute energy interval data allows facilities to use energy information systems to profile aggregate usage, the use of submeters allow the display of actual energy profiles for departments, subsidiaries, divisions or even elements within these organizations. The new thrust of activity based costing initiatives will drive greater demand for intelligent, networked and disaggregated meter data.

Moving from meter or service locations to customers.

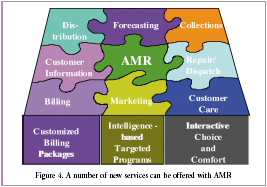

Metering has migrated from a revenue and billing activity to an holistic business enabler. The additional plane of services that an effective AMR system now brings permits utilities to provide additional value added services to their clients. By augmenting monthly revenue reading with interval reading and profiling, customer information systems can be updated to move toward Customer Relationship and Marketing systems. This new addition of depth of services is shown in Figure 4.

Conclusions and Predictions

Based on the trends and expectations of this industry, it is projected that the new initiatives will be instituted or existing processes will modified:

AMR may not be the primary driver for all of these, but will clearly be an integral enabler that permits these services.

About the Author

About the Author

Ronald J. Chebra is the President of RJC Consulting, L.L.C., a Management Consulting Firm providing strategic advisory services to utilities, energy ventures, vendors and suppliers of services to the energy industry. He is the Chairman of the Strategic Leadership Council of the AMRA and is their immediate-past President.

After nearly two decades of existence, the AMRA is the only not-for-profit membership association dedicated to promoting advanced metering, data management and communications technologies worldwide. It serves as an information resource to enable users and suppliers to stay informed about emerging technologies and products, equipment compatibility, industry standards, relevant legislation and regulatory initiatives, AMR trials and deployments.

Within the business model for justification of AMR, there are common drivers, such as the reduction of estimated readings, increasing the accuracy of readings, labor and other cost reductions that AMR brings that form the core baseline economic factors. Yet, some unique need areas within the electric utility have created a focused effort to incorporate AMR as a critical element of a business redefinition process.

According to the Scott Report on AMR Deployments in North America, the total number of AMR annual shipments to electric utilities rose significantly in 2001. This is shown graphically in Figure 1.

While the absolute number of units indicate more shipments to electric utilities, there is a higher percentage of the gas population that has AMR. See Figure 2.

What are some of the key drivers that are creating this growing interest and acceptance of AMR in electric utilities? Some of these value added features beyond monthly revenue reading include a renewed interest in Demand Side Management (DSM), new tariff structures for residential time of use, web presentment of energy information, and a focus on Customer Relationship Management (CRM)

Demand Side Management

Historically, in the height of the oil-embargo during the 1980’s, there was a significant effort to develop energy conservation. Public utility commissions, government and utilities alike collaborated on initiatives to manage power production and distribution to reduce our dependence on foreign oil.

Yet the DSM days of two decades ago have not totally waned, according to the EIA: “In 2000, 962 electric utilities report having demandside management (DSM) programs. Of these, 516 are classified as large, and 446 are classified as small utilities. This is an increase of 114 utilities from 1999. DSM costs increased to 1.6 billion dollars from 1.4 billion dollars in 1999. Energy Savings for the 516 large electric utilities increased to 53.7 billion kilowatthours (kWh), 3.1 billion kWh more than in 1999. These energy savings represent 1.6 percent of annual electric sales of 3,413 billion kWh of reported sales to ultimate consumers in 2000. Actual peak load reductions for large utilities decreased in 2000 to 22,901 megawatts. Potential peak load reductions of 41,369 megawatts were a decrease of 2,201 from 1999. In 2000, incremental energy savings for large utilities were 3.3 billion kWh, incremental actual peak load reductions were 1,640 megawatts, and incremental potential peak load reductions were 3,162 megawatts.”

This renewed focus on DSM (Load Reduction, Peak Shaving, or Load Shifting) is not just to reduce our demand on oil but to help maintain a balance between supply and demand. While each of the initiatives had roots in the energy crisis, many of their results have direct applicability today.

Load Reduction – these initiatives drive the load curve down, lowering the overall consumption. Some of the results of this effort included the evolution of energy efficient appliances, improved lighting units, such as compact fluorescent and insulation/window programs. In 1992 the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) introduced ENERGY STAR as a voluntary labeling program designed to identify and promote energy-efficient products to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Later, in 1996, the EPA partnered with the US Department of Energy for particular product categories, such as computers, copiers, electronics and other consuming devices. Recently the EPA has extended the ENERGY STAR branding to commercial, industrial and residential properties.

According to information from ENERGY STAR, homes that bear the logo have been designed to achieve a 30% savings for heating, cooling and water heating when compared to standard construction practices. This equates to an annual energy savings of between $200 to $400 annually. According to the National Energy Policy Act of 2001, 4.8% of disposable family income is spent on energy

Peak Shaving – Since mass storage of electricity has not yet been perfected, capacity must be provided to support peak consumption and demand. With the advent of distributed generation capabilities, many large users are beginning to use these reserves to offset peak demand charges. To achieve accurate measurement of the utility supplied energy and self provided energy use, a majority of states in the US have rules that govern the use and permission of Net Metering.

According to US Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, “Net Metering allows the electric meters of customers with generating facilities to turn backwards when the generators are producing energy in excess of the customers’ demand, it enables customers to use their own generation to offset their consumption over a billing period. This offset means that customers receive retail prices for the excess electricity they generate. Without net metering, a second meter is usually installed to measure the electricity that flows back to the provider, with the provider purchasing the power at a rate much lower than the retail rate.

Net metering i s a low-cost, easilyadministered method to encourage customer investment in renewable energy technologies. It increases the value of the electricity produced by renewable generation and allows customers to “bank” their energy and use it a different time than it is produced giving customers more flexibility and allowing them to maximize the value of their production. Providers may also benefit from net metering programs because when customers

are producing electricity during peak periods, the system load factor is improved.”

As of late summer 2002, thirty six (36) states had policies in place to deal with the concept of net metering. This is shown in Figure 3.

Load Shifting – While the concept of net metering allows the use of exisiting meters,it is expected that the impact of this initiative will be a need to upgrade meters and the communications between the utility and end user.

New tariff structures and services for residential customers

So much of our behavior is driven by time. From the morning alarm clock to the 6:18 am train, our life is oriented around time-based activities. There are many programs that have successful linked an economic benefits with a shift in time of use. For example:

On the New Jersey Transit northeast rail line serving New York City, the off-peak transit rail rate is 25% less if travel does not take place during the peak commuter period between 5:45 am and 10:00 am inbound and 4:00 pm to 8:00 pm outbound.

Travelers who pay cash at the tollbooths on the New Jersey Turnpike have a flat, time insensitive rate, based on distance traveled. E-Z Pass transponder travelers automatically participate in a time of use plan. Using this electronic tag, the toll rate is 12% less than the cash rate during the peak times of 7:00 am to 9:00 am and 4:30 pm to 6:30 pm weekdays. Users during the off peak period and realize a 20% discount.

On a typical cellular calling plan, calls placed from 9:00PM to 6:00 am Monday through Friday and from 9:00 pm Friday to 6:00 am Monday during the “Weekend and Evening” rate pay and are less than 50% less than the on-peak rates.

The overall consumer acceptance of a time of use incentive/penalty approach appears to be growing, especially when the ability to modify behavior can result in a tangible financial benefit. Yet, there has been little penetration of Electric Residential Time of Use in the United States.

In a recent study performed for a Fortune 100 firm, RJC-Consulting, LLC surveyed over 100 electric utilities covering the top 50 utilities that are investor owned (IOU’s) and at least one utility from each state to determine their current residential Time of Use (RTOU) program and the number of participants in these programs. Except for a few major initiatives, the percentage of customers currently participating in these programs, was less than 1%. A number of reasons for this lack of acceptance was cited in the report. They included: a lack of promotion of these on the part of the utility; the structure of the program itself, including the start-up costs, and cost spread between peak and off peak rates and the incremental cost of the TOU meter itself that was passed on directly to the consumer. All these factors contributed to the lack of incentive for consumers to justify a change from a flat rate to a TOU rate. Virtually all the programs evaluated did not give the customer any real-time indication or tangible dollar amount one could save by shifting load to an off peak time.

Energy efficiency comes into play often when individuals are making decisions about certain products. However, the energy consumption savings projected over the life of the product can confuse many consumers. This is especially true when they are forced to evaluate the future value of an investment they must make today with little information about their historical usage. Saving $15 a month on a new refrigerator must be compared to what is being spent today on the same appliance, and that information on an individual element is at best estimated or projected. The energy consumption sheets on products have a value that is similar to the estimated miles per gallon displayed on the specification sheet of a new vehicle. Actual results may vary based on individual consumer use habits.

Obviously, when the cost of energy is high, the trend would be that consumers would buy more efficient products. In a stable energy cost environment, unless there is a way to inform customers about the actual cost of the energy used by the device, the weight of the a higher efficiency choice argument may be minimal. In a volatile energy cost market, consumers need receive current electricity costs in order to make efficiency decisions or to make adjustments to their energy use to take advantage of any time of use service that is available.

Further, there are few devices that automatically modify their operational characteristics based on the actual time of day. When non time responsive loads are operated in a TOU environment, the load is averaged across the off-peak and on-peak rates. Often the higher cost of on-peak electricity masks any savings that may be realized during the off peak period. Therefore, consumers may not recognize the benefits of investing in technologies that operate or shift load to off-peak consumption periods or to ensure that the clock within the device is kept accurate.

The advanced services provided by more sophisticated metering systems can bridge this gap by providing both time sensitive energy use information to consumers and by being the gateway to network devices that measure, calculate and display energy costs. Often this is an element of an AMR system that is difficult to quantify in an economic model.

Information grade metering can complement revenue grade metering

While the growth of AMR for revenue metering is apparent, an underserved area of AMR in the information grade or submetering arena. Although once perceived as a threat to the metering department, these element monitoring devices and units are now gaining new respect.

Just as 15 minute energy interval data allows facilities to use energy information systems to profile aggregate usage, the use of submeters allow the display of actual energy profiles for departments, subsidiaries, divisions or even elements within these organizations. The new thrust of activity based costing initiatives will drive greater demand for intelligent, networked and disaggregated meter data.

Moving from meter or service locations to customers.

Metering has migrated from a revenue and billing activity to an holistic business enabler. The additional plane of services that an effective AMR system now brings permits utilities to provide additional value added services to their clients. By augmenting monthly revenue reading with interval reading and profiling, customer information systems can be updated to move toward Customer Relationship and Marketing systems. This new addition of depth of services is shown in Figure 4.

Conclusions and Predictions

Based on the trends and expectations of this industry, it is projected that the new initiatives will be instituted or existing processes will modified:

- AMR will continue to experience rapid growth and deployment as new services are provided to the mass market;

- Advancements will be made to make Time of Use more attractive and beneficial to residential consumers;

- Devices will migrate toward including next generation energy intelligence, including time of use responses, and individual kilowatt hour meters that will be networked within a premise;

- More intelligent communications between the utility and the end user will permit interaction among the utility, consumers and devices;

- Imbedded intelligence will grow enabling more holistic energy environments.

AMR may not be the primary driver for all of these, but will clearly be an integral enabler that permits these services.

About the Author

About the AuthorRonald J. Chebra is the President of RJC Consulting, L.L.C., a Management Consulting Firm providing strategic advisory services to utilities, energy ventures, vendors and suppliers of services to the energy industry. He is the Chairman of the Strategic Leadership Council of the AMRA and is their immediate-past President.