It’s a well-known fact in today’s society, information equals power. Without information, the ability to make educated decisions about what to do and when to do it is hindered. This applies to all aspects of our work and life – and now it is beginning to impact the way we consume energy...

Clearly the statement above is a phenomenon that most utilities understand well and grasp the potential benefits of. Utilities across the country have embarked on Smart Grid projects that promise the possibility of providing this ‘power’ to consumers; however, the effects of these efforts are not being immediately realized and the consumer is far from feeling empowered. In fact, in some cases Smart Grid projects have provoked fear and confusion amongst consumers rather than instilling a sense of empowerment. The massive investment in infrastructure upgrades and technology to drive the Smart Grid is being called into question due to the inability of utilities to communicate precisely how these technologies will empower consumers to make better decisions.

Readers of this article are arguably part of the most informed set of the population as regards Smart Grid issues. However, for the general public, industry terms such as ‘demand response’ and ‘load balancing’ are foreign concepts and require significantly more explanation before they make it into mainstream conversation, let alone into meaningful changes in behavior. Tools that provide simple accessibility to information will be the strongest aid for these programs to have a lasting affect on consumer behavior.

Energy Monitoring Moves Into the Living Room

Historically, the traditional interactions that utility companies have with consumers are limited to two instances: (1) when the consumer gets their monthly bill and (2) in the event of a power outage. As the Smart Grid roll-out becomes a reality, utilities are adding to the touch points of information they are gathering from and delivering to consumers.

Electric meters – smart or not – provide very accurate information in precisely the wrong location. Most homeowners often go years without actively noticing their meters – because there has never been a need to do so. In-home displays (IHDs) hold the promise of bringing this information into the environment where the consumer actually makes decisions on how to interact with their energy consumption. Transitioning to a world where IHDs are prevalent and deliver the promised benefits requires utilities to focus on what works. Several factors determine what works and what doesn’t, as summarized in the paragraphs following…

Affordability is an important factor involved in ensuring a broad adoption of IHDs. Ideally, the devices are made available at no up-front cost to all consumers. There has been an aversion by US consumers to spend discretionary dollars on energy saving products and services. Whether via subsidies at retail or direct distribution, utilities need to work with manufacturers of IHDs to provide a cost effective solution that has the broadest consumer appeal. For manufacturers, this means focusing on the core functionality and building features into devices that are sure to provide tangible value to the consumer.

In-home displays must be simple to install. It is beyond the resourcefulness of most consumers to ask them to replace their existing thermostat or access their electrical panel. Requiring a professional installer is not only inconvenient for the consumer, but also defies the rule of being affordable. The devices have to be ‘plug-and-play’ and work without an intense study of a user manual.

The data presented on IHDs should be intelligible. Kilowatt-hours are not part of our daily vernacular and most consumers would have a hard time translating what this means. Data should be made available in metrics that are widely understood – dollars and cents vs. Kilowatt-hours.

IHDs should be glanceable. The display should represent the most important information in a form that can be read from across the room in less than a second. This highly summarized view of information enables consumers to process all the data they need to know and what to do with it at a glance rather than digging through multiple screens or graphs. ‘Glancablity’ allows for simple explanation on the function of a device to any consumer. Any ‘drill-down’ information, meaning detailed descriptions of the data, should be presented by actively engaging with the device or on a separate screen such as a smart phone or web-browser.

The data shown on any IHD should be dynamic. Displayed data should change often enough to remain interesting and instructive to the consumer. This not only makes for a more engaging experience, but also helps build a trusted relationship with the device because consumers are apt to react to it more often.

It is important for IHDs to be situated appropriately. The display should be positioned properly in order to provide information at the decisional moment of energy consumption. Smart phone and web browsers offer rich displays of data, but often not where consumers are making choices on how to use energy. The IHD can be placed virtually anywhere in a home, allowing consumers to position the device in the periphery of our senses in order to provide continuous information without being distracting.

IHDs must be unavoidable. It is necessary for the display to cut through the visual clutter of the home to promote mindfulness around energy use. It is important that they are designed not to mimic other devices in the home, but stand out amongst the vast array of screens that in consumers’ homes today. This is perhaps the most important element that will lead to the success of an IHD deployment. The device must also endure the possibility of being placed in the ‘junk drawer’, a place where many other gadgets end up.

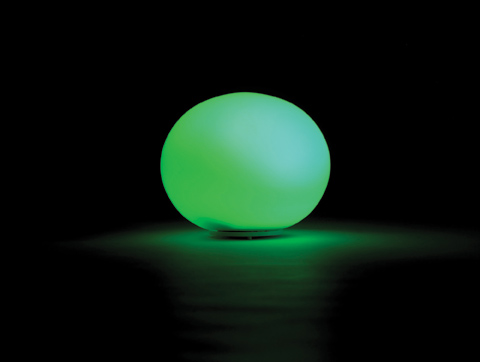

Energy Orb glows varying shades of color representing

energy consumption and demand on the grid

Baltimore Gas & Electric Tests the Energy Orb

Ambient Devices recently introduced the Energy Orb to address what works for utilities and their customers. The device’s imbedded intelligence and network connection enable real-time feedback from the energy grid, which directly affects the users energy consumption behavior. These devices have been deployed by over a dozen utilities in both residential and commercial demand response projects worldwide to show the load on the grid, manage demand and avoid brownouts.

In the summer of 2008, Baltimore Gas & Electric Company (BG&E) embarked upon a unique experiment designed to understand how customers would respond to a variety of smart grid stimuli. Called the Smart Energy Pricing (SEP) pilot, it ran from the beginning of June through the end of September. It tested two types of dynamic pricing rate (critical-peak pricing and peak-time rebates) and two types of enabling technologies, the Energy Orb and switches for cycling central air-conditioners.

Since the SEP pilot was focused on measuring changes in customer behavior, it was designed in conformity with scientific principles of accurate measurement. It featured a variety of matching treatment and control groups that were randomly selected and their load profile was measured before and after the introduction of the smart grid treatments. Altogether, 1,375 customers participated in the pilot. Of these customers, 354 were in a control group, 401 on dynamic pricing rates without enabling technologies, 278 on the Energy Orb in conjunction with dynamic pricing and the remainder on the Energy Orb and cycling switches for central air conditioners.

The plug-and-play orb can be setup anywhere

in the home, allowing consumers to easily view

he dynamic information they care most about

without having their everyday lives disrupted.

Customers in the control group stayed on standard rate, which charged 15 cents per kWh around the clock. Those on the critical-peak pricing rate faced a price that was nine times higher on the peak period on a dozen days that were designed to simulate very high price conditions in the PJM wholesale market. Prices during off-peak hours were about six cents per kWh lower than the standard rate. Two types of peak-time rebates were tested, featuring levels that were nine times higher and twelve and a half times higher than the standard rate.

Econometric analysis of the experimental data yielded some remarkable insights. Customers on dynamic pricing without enabling technology showed the same pattern of price responsiveness whether they were on critical-peak pricing or peak- time rebates. On average, they lowered their usage during critical-peak periods by 19.6 percent.

When they were equipped with the Energy Orb, their price responsiveness went up to 24.9 percent. It is noteworthy that the Energy Orb did not control any appliance in the home, like the cycling switch, but it conveyed actionable information a meaningful and simple way to the human mind. Furthermore, when the cycling switch was added to the Energy Orb, the responsiveness went up to 30.4 percent.

In sum, the SEP experiment showed the power of dynamic pricing, especially when carried out with information-conveying technologies such as the Energy Orb. The experiment also addressed the major variables in changing a customer’s energy consumption behavior:

- Affordability – Participants in the BGE pilot were provided with IHD’s free of charge.

- Installation – The IHDs were simply mailed to the consumer’s home via regular mail delivery and were able to receive real-time data ten minutes after being plugged into the outlet.

- Intelligence – Instead of showing a vast amount of data, the IHD only displayed colors to represent the data.

- Glanceability- Data was presented through varying shades of color representing dynamic data that could be absorbed at a glance.

- Dynamic data - During the pilot, data was called throughout the summer allowing the IHD to maintain relevance.

- Location – Participants were able to position the device where they were able to gain the necessary information at the decisional moment of energy usage.

- Design – Unlike many other smart IHDs, the Energy Orb is designed to stand out amongst other devices in the home.

Utilities Must Communicate

IHDs serve as a communicative approach for utility companies to relay information to customers about energy consumption and demand. By establishing a relationship, utility companies can forewarn their customers that supply and demand on the electric system may be reaching a critical point or that a demand response event has been called. By outfitting consumers with an easy-to-use enterprise or in-home tool for smart energy consumption, utility companies will see power spread more evenly through each day and consumers will begin to shift their usage to off-peak hours, resulting in relief for the grid and energy bills.

About the Authors

Pritesh Gandhi is CEO and Co-founder of Ambient Devices, Inc. in 2001 and serves as Chief Executive Officer. Mr. Gandhi has more than 15 years of experience building companies focused on delivering innovative consumer applications across multiple industries. In addition to overseeing Ambient Devices operations and strategy, Mr. Gandhi has been the driving force behind the company’s expansion into the In-Home Display market. Through his direction and management of Ambient’s retail partnerships, he has brought over one million units to the shelves of retailers including Best Buy, WalMart and Brookstone.

Pritesh Gandhi is CEO and Co-founder of Ambient Devices, Inc. in 2001 and serves as Chief Executive Officer. Mr. Gandhi has more than 15 years of experience building companies focused on delivering innovative consumer applications across multiple industries. In addition to overseeing Ambient Devices operations and strategy, Mr. Gandhi has been the driving force behind the company’s expansion into the In-Home Display market. Through his direction and management of Ambient’s retail partnerships, he has brought over one million units to the shelves of retailers including Best Buy, WalMart and Brookstone.

Mr. Gandhi received his BS and MBA from Boston University, where he concentrated in Marketing and Entrepreneurship. While pursing his MBA, Mr. Gandhi wrote the business plan for Ambient Devices and co-founded the company shortly after graduation.

Ahmad Faruqui is a Principal at The Brattle Group and one of the nation’s leading experts on the smart grid. He helps clients assess the economics of dynamic pricing, demand response, advanced metering infrastructure, and energy efficiency. He pioneered the use of experimentation in understanding customer behavior and his early work on time-of-use pricing experiments is cited in Professor Bonbright’s textbook on public utility rates. The author of four books and more than a hundred papers on energy policy, Faruqui holds a doctoral degree in economics from the University of California at Davis.

Ahmad Faruqui is a Principal at The Brattle Group and one of the nation’s leading experts on the smart grid. He helps clients assess the economics of dynamic pricing, demand response, advanced metering infrastructure, and energy efficiency. He pioneered the use of experimentation in understanding customer behavior and his early work on time-of-use pricing experiments is cited in Professor Bonbright’s textbook on public utility rates. The author of four books and more than a hundred papers on energy policy, Faruqui holds a doctoral degree in economics from the University of California at Davis.