Conventional forms of power generation have a proven and established value chain and easily identifiable (and more importantly, finite) set of levers to determine the technical viability and financial profitability of projects – whether in the generation or in the T&D domain. Renewable forms of generation, however, pose a different set of challenges, given that as yet, there is no ‘well-baked’ set of business rules other than those established for more conventional energy sources such as hydroelectric and nuclear. In this second part of our look at the future of renewables growth, we explore the intricate relationships between developers, regulators and investors and how those relationships affect the outcomes of proposed projects – and their success or failure.

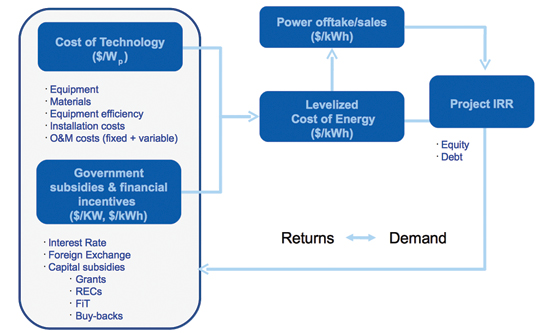

If we look at the overall energy demand and supply relationship1, it is clear today that no single entity calls all the shots - this is especially true in the Renewable Energy sector. This new model has, however, evolved somewhat in the aftermath of the economic meltdown with two primary levers emerging:

- Cost of Technology (controlled by the major suppliers, especially true in the case of solar and wind suppliers); and,

- Expected Return on Investment (ROI) – in the form of project IRR (Internal Rate of Return) – by the investors.

The rest of the value chain (above) had to align with the key drivers. However, the falling price of technology (consider the drop of nearly 30% in solar modules alone!) together with a major reset in investor expectations (project IRR threshold for a PE fund is 18%) have refocused attention on other levers. Today, a promoter of renewable projects has an array of opportunities where it can be effective – from acting as a pure-play project developer (i.e., selling the project to a third party after development) to acting only as an EPC (Engineering, Procurement & Construction) contractor, to being the complete asset owner/operator. Somewhere in between is the notion of a Systems Integrator.

Integration of Storage Solutions

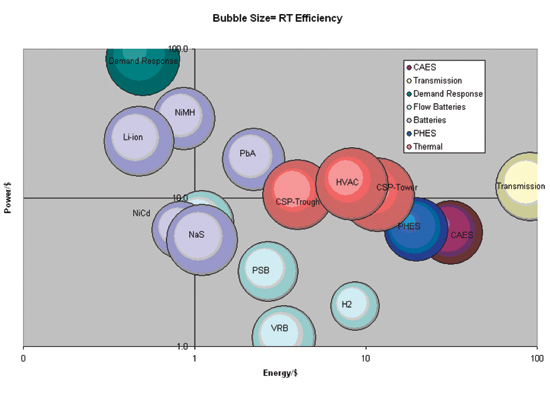

A key toward combating intermittency and capacity concerns of renewable sources of generation – primarily solar and wind – is to integrate storage devices into the overall generation schema. Battery back-ups in small-to-micro solar applications have been around for a long time. However, there are very few commercially viable solutions that are truly dispatchable. Integration of storage helps to improve grid optimization of bulk power generation from renewable sources in addition to improving plant capacity factors. For example, there have been solar thermal projects where molten salt has been used as the storage medium, but economic feasibility usually makes such solutions prohibitively expensive.2

As a first step toward determining the amount of energy storage that should be added to a grid with intermittent resources is to ascertain the marginal cost of generation. The brief analysis illustrated here offers a snapshot of various options available today. Another option that is rapidly gaining momentum among generation planners is the integration of base load generation – mostly gas – with a large wind project.

Moving Down the T&D Food Chain

One of the ways to demonstrate near-term positive impact of renewables – in the form of energy efficiency – within the T&D grid infrastructure is in its penetration at the Distribution level. Such integration can be part of a wider Demand Response and Demand Side Management program. A great example of such an implementation is PSE&G’s program, announced in 2010 to integrate solar PV modules at the distribution pole level. The assumption in such implementations is that the incumbent utility’s distribution system is equipped to handle spikes (and troughs) of intermittency during peak hours. An additional benefit of distribution-level “behind the fence” application (i.e., with a net-metering option) is not having to deal with transmission-level ISO issues which will help in quicker execution of projects.

The ‘Catch-22’ Loop

It’s the classic Catch-22 situation in the renewable sector today between investors and developers. Investors are looking for projects that are “shovel ready”. However, for a project to be ready for construction, a developer has to spend an average of $200-$250K/ MW – which most investors are simply not willing to put up. This is a logjam that needs to be broken. Another aspect that developers need to be mindful of is the fact that most investors are not interested in one or two small (e.g., <500KW in solar PV) projects. A portfolio of 5-10MW (minimum) is a much wiser approach toward developing a portfolio of projects – at least in case of solar.

Dependence on Government Subsidies

Finally, the renewable energy sector has to eventually wean off government subsidies. The independence from state handouts (of one form or another) will not happen immediately and will require a concerted effort between:

- Regulators… who will help lay out long-term clear market rules to facilitate growth;

- Developers… who will have to reset their ROI expectations;

- Suppliers… who will be forced to improve technology efficiencies constantly to drive manufacturing costs down. (Even a 15-20% reduction in ‘per MW’ capital cost increases the project IRR by nearly a full 1%, in the case of a solar project); and,

- Investors… who will need to rethink their IRR thresholds and consider a more collaborative approach with project developers right from the project development stage.

Potential Solutions in Solar PV Project Development

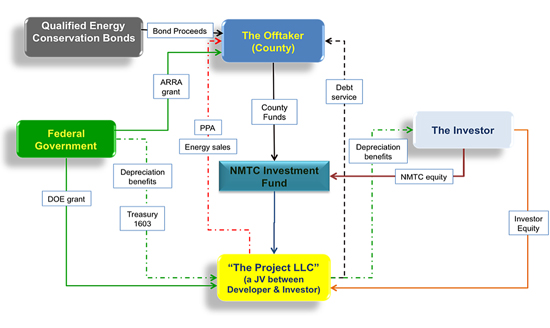

The nature of renewable project development is such that no single model can fit every proposed project. Here the author illustrates3 a scenario of a Public Private Venture (PPV) for a solar PV project that may offer each of the key stakeholders in the value chain various options to consider. PPV participants are the developers, the energy off-takers, local authorities, suppliers and investors. Typically solar PV projects may be categorized under two principal categories:

- Ground-mount systems, and

- Rooftop projects.

The “off-takers” – that is, the entity (or entities) buying the energy – which may be a utility (e.g., a local distribution company); a commercial establishment, such as large warehouse, hospital, parking garage, etc.; or a local government owned and operated facility (e.g., state-/county-owned buildings, schools, etc.). The example given here is a unique, but proven, model for a large rooftop project at a county-owned facility.

It is important to note specific traits of the PPV model – mostly how the funding resources were optimized to make a project financially meaningful to the investor/s. At the same time, it is critical to appreciate how a project can leverage and optimize the two big incentives the US Treasury and the USDOE offer today as investment incentives:

- The 1603 Treasury Refund for renewable projects, and

- Application of the accelerated depreciation benefits.

Large Rooftop4 System: A Low Project Cash Flow Challenge

Let’s consider the role of various participants in this project to better appreciate how each party worked through various challenges by optimizing the resources at hand.

The Developer: Was presented with a classic example of what most solar project developers struggle with today – a PPA which has a low starting tariff (below $0.08/kWh) on top of being in a region that does not offer Solar Renewable Energy Credits (SRECs) that could have provided the added “kicker” to energy sales. Thus, the pro forma presented a low project cash flow situation – and yet the need to create a model that attracted equity investors was imperative. One positive aspect of the PPA was the fact that the off-taker (the County) had a AAA credit rating – a vital statistic to any investor!

The Investor: This is where leveraging tax equity benefits kicks in. With corporations sitting on record amount of cash and profits today, the classic tax equity investor is starting to emerge again (which had been mostly in a state of hibernation the past two years).

The Off-taker: The project was envisioned as a “crown jewel” in this particular county’s push toward a leadership role in the country in owning renewable energy assets in its portfolio of facilities. However, the opportunity didn’t come without dilemmas! The retail energy rates were low enough in this state that it posed a challenge to justify paying a higher tariff to the solar energy provider – JUST to have a showcase project. Moreover, in anticipation of this monumental project, the County had already started down the path of reinforcing the roof to make it ready for the solar PV infrastructure. Needless to say, a lot was at stake.

The Supplier/EPC: The equipment supplier and the EPC partner had to be in close concert to constantly improve upon the cost/ Watt factor in order to compensate for the challenging economics of the project.

The Utility: Project completion is incumbent upon successful interconnection with the local utility for net-metering purposes. Here was a situation where the local distribution company had never tried to integrate intermittency of this magnitude (i.e., 2MW or more of solar PV) into its grid.

The Solution – Optimization of Stakeholder Expectations

After several rounds of discussions regarding making the project financially viable, here’s where the County stepped in to not only provide some incentives and guidance, but also to take a leadership role – primarily to make sure specific risk parameters were adequately addressed and the project became attractive to all parties concerned:

a) The County issued a bond to cover debt (approximately 15% of the total project cost), a process that was fast tracked by the county;

b) The County applied for and received significant DOE and ARRA grants (for approximately another 15% of total project costs, which could be applied toward capital procurements);

c) The County was also instrumental in lobbying to the National Development Council (NDC) for an allocation of New Market Tax Credit (NMTC) that accounted for almost 20% of the project cost;

d) The PPA allowed a flip-structure – where the equity investor could sell the project after a pre-determined number of years for the County to own the asset for the rest of its useful life;

e) The County worked hard with the developer to make sure it qualified for the 1603 refund; and,

f) Topping it all, the County as the off-taker became the key facilitator between the developer/EPC team and the distribution utility to ensure adequate management sponsorship at all levels to move the process forward.

This meant the equity investor only needed to put up less than 50% of the total project cost after accounting for the 30% refund from 1603 after production started. Historically, private equity funds have expected a minimum IRR of 18-20%. In this case, to compensate for the lower IRR of the project, the equity investor re-modeled its return expectations by leveraging the up-front tax equity benefits and the ability to depreciate the eligible asset base a full 100% in Year-1 to gain a fairly healthy return on equity.

Rather than accounting for a large upfront development fee, which would have made the project even more difficult to justify, the developer formed a joint venture with the investor. In this arrangement the developer continued to have a carried interest in the cash flow throughout the life of the project in return for a lower expectation on the development fee.

In the end, rather than each stakeholder maintaining a rigid set of expectations, each party came to the table to work toward a common goal by being a creative in structuring the transaction so that no one party would be left feeling short-changed as a result of its willingness to compromise and participate – and it worked! (The PPV Model is depicted in the illustration below.)

About the Author

Koustuv Ghoshal is Managing Partner at Inspirra Energy, an independent investment banking and industry advisory firm focused on the mid-market renewable project development and energy efficiency sectors globally. Each of its principals has deep industry experience in energy industry market research, power project development, and project funding advisory. Koustuv can be reached by phone at +1-469-361-2120 or via email to kghoshal@inspirra.com.

1 Adapted from Linx•AEI Consulting (Sep 2010).

2 Pumped hydroelectric and CAES technologies are proven market solutions in the hydro power domain.

3 Based on actual business models for large solar PV projects in the US that the author has been associated with recently, representing the developer and the investor components of the value chain

4 By this author’s definition, any solar PV rooftop project of more than 2.0MW is a large project. However, there are not many projects of that size in the US today.