The role of a program manager in utilities has complexities worth exploring as part of a role clarification or “swim-lane” discussion.

At a very high level, the objective of the program manager is simple. Utilities hire program managers to improve the likelihood that their various programs will be delivered as intended. That has parallels with another business endeavor, which is building construction.

In the construction business, some architects design buildings, construction and project managers who guide the construction process and all the various trades who perform the construction.

The primary role of the architect is to design the building to meet the needs of the client funding the project. Therefore, the architect’s main focus is on the end product. If architects could snap their fingers and make their buildings magically appear, most would be happy to just skip over the messiness of the construction process.

On the other hand, the role of the construction manager is to guide the construction process to achieve the architect’s vision. Unlike the architect, the construction manager can’t avoid the messiness of the construction process.

In utilities, asset management teams are like the architects. Asset Management’s role is to develop and secure funding for programs that support the utilities’ goals. Portfolio management groups and the various program managers are like construction managers in the building industry, their role is the guide the process of delivering the programs and projects to achieve their individual and collective objectives.

This simple analogy is useful because it clarifies some of what the different roles should be expected to do as well as things that are outside their swim lanes.

For instance, if a construction manager does not like the look of a building, that does not mean they are entitled to change it. The role of the construction manager is to respect the architect’s vision and build the building efficiently, even if they think it’s hideous.

However, that does not mean that architects hold all the decision-making rights. The construction manager and the building trades have obligations to respect regulations and building codes and may be constrained by budgets and schedules. Therefore, architects don’t get to do whatever they want.

The answer is that collaboration between architects and construction managers is essential. However, it is helped by understanding how to work through situations where something has to give.

Shared resources – a critical distinction

When program and project manager’s roles are being discussed, a critical difference is that the role changes when the PM has authority over the deployment of resources, or not.

One option for program or project management is to set up the project as a “standalone” undertaking, assign a person to the role of PM and provide them with the authority over the resources needed to complete the project. Under this model, the PM has the authority to bring on the resources they need to complete the different phases of the project and they can let resources go when they are no longer needed. Under this operating model:

- The PM can be held accountable for delivering the project.

- The PM monitors progress and moves resources around as needed to complete the project.

- The PM is the single point of accountability for decisions on the project.

Standalone projects or programs are not the norm in utilities. In utilities, it is more common to see projects and programs sharing the various resources needed to complete the work such as engineering, design and field execution crews. Under this model, program managers are expected to monitor and guide the program towards the program goals, but the PM does not have the authority to direct resources to work on their projects or programs and not work on other programs. Under this model:

- The PM cannot be held individually accountable for delivering the work because they do not have the authority to deploy resources as they see fit.

- The PM monitors progress and is the primary point of contact for information on the status of the program or project, but they are not the single point of accountability for all decisions affecting the work.

- A PM should know if they have lost resources on their program to higher priority work, and should be able to report that fact, but may not be able to change it.

- The PM guides the advancement of the program or project work. In some cases, that means they make decisions, but in other cases, they are limited to making recommendations that others are accountable to accept or reject.

Something has to give

A requirement that shapes the role of the program manager, is that they must bridge the gap between strategic goals and the reality on the ground.

A good example is the cheap, fast, quality triangle. The idea is that somebody may want all three (cheap, fast, quality) but they won’t get all three. There is an inevitable trade-off when there is pressure on one side of the triangle.

The implication for program (and project) managers is that they should always know where to adjust when situations come up where something has to give.

- Running out of budget - Change scope, quality or speed?

- Under time pressure - Spend more money or compromise quality?

The alternative to dealing with this issue pragmatically is just hoping everything works out. Unfortunately, hope is not a leadership strategy. As the well-known quote says, “No plan survives contact with the enemy.” In business, the “enemy” is the reality on the ground and the curveballs the business environment throws at the operations.

Some companies put project and program plans together, roll them up into an annual business plan and hope it all works out, and if they are lucky, it might work (sometimes).

The more realistic and pragmatic approach is to acknowledge that even the best plans won’t completely survive contact with the reality on the ground, and when adjustments are required, the role of the program manager is to know what should give and provide the best guidance. A PM should know how to adapt to the circumstances and come as close as possible to delivering the important elements of the program they are responsible for.

All estimates are wrong, it’s just a matter of degree

Estimates are approximate calculations or judgments of the value, number, quantity or extent of something.

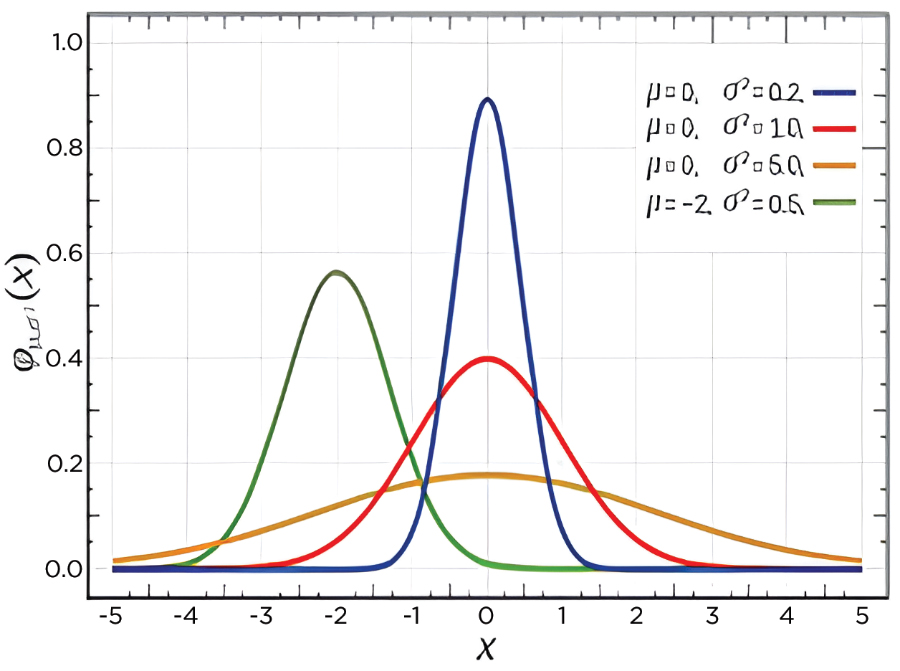

At the same time, the time to complete tasks that are done multiple times will be plotted on a distribution curve of some shape. Also, different types of tasks or jobs have different distribution curves. Some jobs have very tight distributions around the mean, (blue curve) and a good estimate of the average can be used to plan and schedule work without much difficulty.

On the other hand, work that has a wide distribution (beige curve) means that an estimate of the average could be significantly different from reality on any given day. That does not mean the average is wrong, or the estimate is poor.

The critical thing for anyone involved in planning and scheduling processes is to understand what estimates and averages represent, when to use them, and when to not use them.

- A provincial average estimated time to complete a job may be very close to the actual over several repetitions, so it may be ideal to use for annual investment planning.

- However, that does not mean that an individual occurrence of the job will be close to the average.

- • If the time it takes to complete one job is bang on the average, it’s a fluke and nothing more.

- Throw enough darts at a target blindfolded and one is sure to hit the bullseye.

- An estimate (or previous average) is not a target. Estimates are a valuable point of comparison, but to maintain an average, 50% of all repetitions of a job must come in below average to make up for the ones on the “harder” side of the curve. Therefore, the average should not be the target.

- Good tactical planners and schedulers make adjustments to the estimated “average” situation to optimize plans and schedules. They don’t blindly schedule using the average.

- Some jobs will be quicker than average (e.g., work is bundled with other work, and the device being worked on is already open and prepared).

- Some jobs will be longer than average (e.g., travel time is demonstrably longer than the average allowance, access is a nightmare, etc.).

Unconstrained vs. constrained perspective

In capital-intensive industries, one of Asset Management’s responsibilities is advising the leadership of the company on maintenance strategies designed to optimize the life cycle costs and reduce the operating risk profile of the company’s assets.

That means that asset management teams should have a perspective on the best maintenance strategies for different assets given the way the company uses and maintains its assets (the duty cycle) and the current age and condition of the assets.

Going into a strategic planning cycle, it is Asset Management’s responsibility to evaluate what the “right” level of maintenance is to achieve the company’s business goals.

This should lead the asset management team to develop an unconstrained perspective of the best maintenance activities to do so that they can advocate for the ideal level of funding to optimize values for the company and stakeholders.

However, what Asset Management wants to do and what they can do are not always the same thing. Asset management teams routinely discover that mundane considerations such as budget and resource constraints get in the way of doing all the asset maintenance work they would like to do.

This gives rise to the idea that when the plan that’s ultimately implemented is constrained, Asset Management’s role is to make risk-based decisions on how to scale back plans to do the best they can under the constraints they have been given.

The complication for program managers is that asking, “What are we going to do in the next few years,” (while a legitimate question) does not have a simple answer.

- Asset Management can provide an unconstrained view of what they believe the company should do.

- Asset Management could provide a perspective of what they think the constraints will be and what the company will do (but they don’t make that decision).

The complication is that no view of future years is “right” or “wrong,” or empirically provable.

Both the unconstrained and constrained views of future program work are opinions. They are not facts. It is the planning equivalent of driving into the fog.

The implication for program managers and asset management teams is that they need to embrace this reality and design planning processes that allow them to move forward making the best plans possible while understanding that the view is imperfect, and things can change.

Dealing with uncertainty and inevitable variability

The conclusion is that planning processes need to be designed to deal with all the unknowns that could affect plans and the inevitable variability in how things unfold in the real world.

Planning is also made more complicated in situations where the programs and projects are sharing resources. Planning and project management are always easier when the PM can bring on resources when needed and release them when they are not. However, utilities tend to have workforces that come to work every day whether a project needs them or not, and the company wants to fully utilize its resources to minimize operating and maintenance costs. That leads to the desire for workforce flexibility, for crews to move from job to job without being tied down to one project or program.

While perfectly logical and very achievable, sharing resources adds another dimension of variability for PMs to deal with. It means that the plans for one program or project are not only subject to the variability within that project but they are also impacted by the variability in all the other work going on around them.

Thriving in this kind of environment requires flexibility which comes with implications.

Even good plans that are fundamentally sound should not be considered 100% locked in. Locking in a plan is like building a dock and hoping the water level won’t change. It may appear to work for a while, but it won’t in the long run.

Just like building a dock, good program managers should know how where the flexibility is in their program. They should know (in advance) how they should flex to deal with the inevitable inaccuracies in estimates and inevitable variables in work execution.

Strategically it should be straightforward to identify and manage the flexibility in any work program. Intuitively people understand that some pieces of work are just so important, that they should still get done even if the cost is higher than estimated. Other work may be required “sometime” in the next few years, but if budgets are constrained there is not much harm in deferring it until next year. The implication is that dealing with variability by being flexible boils down to pragmatic adjustments that align with what’s important.

The program manager’s role is to provide insight

The reason program managers exist in utilities is simple, it is to improve the likelihood that the objectives of the various programs in the company will be realized.

However, program managers operate in a kind of “middle office” between asset management teams, who are like the architects who strategize program objectives and funding, and the work execution teams.

Interestingly, most utilities design their organizational charts so that groups like Asset Management, Portfolio Management and work execution groups are peers. The implication of that is that they are expected to collaborate to achieve the company’s goals, but the company has not given any group authority over the others.

This all means that an individual program manager is in a role where the objective is

to guide a program to meet its goals while not having decision-making authority over the design of the program or the ability to direct resources to work on the program. The PM does that while being surrounded with estimates that will never be perfect, variability in field execution, unforeseeable curveballs from the weather and plans that are built from flawed databases.

The implication for the program manager is to realize that their fundamental role is to provide insights that influence the organization around them. Good PMs position themselves so that they can:

- Provide insights about what is happening in the field to Asset Management so AM can improve their work program strategies.

- Provide insight into the strategic objectives of the program to tactical planners, schedulers and execution teams.

- Provide insight into trends impacting the program to leadership in various LoBs.

PMs who fail to understand that their role is to influence the organization through the power of their insight may fall into the trap of thinking their role is to control the other parts of the organization involved in the end-to-end process, or they see fault and blame in the inevitable variability around them. Struggling PMs may become more rigid when the right answer is to become more flexible.

Accountability for unit costs of work is a good example to use to understand the difference between insights and control. On one hand, a program manager cannot be accountable for unit costs. After all, Asset Management decides what needs to be done and the field execution groups are accountable for their productivity in completing the work.

On the other hand, the program manager can and should be accountable for having insights into unit costs. The PM should:

- Understand the unit cost impact of decisions made in Asset Management.

- Evaluate the unit cost implications of more tactical planning and scheduling decisions, whether they make them, or others do.

- Monitor the actual unit costs and develop insights into unit cost trends so they can provide those insights to all stakeholders.

That means that as the primary point of contact for a program, the program manager is accountable for being able to provide insights in response to questions about their program. That does not mean the PM is accountable for fixing a problem with unit costs. It means that a PM should be able to confidently explain that rising unit costs are due to material cost increases or that productivity is lower than it was last year, but it is not their responsibility to address the underlying issue.

Duncan Kerr is a managing partner at The Engine Room Group, a utility-focused operational excellence firm that has substantial expertise in the evaluation and implementation of transformational utility projects covering asset management, strategic planning and scheduling, work execution, cost savings and operational excellence.